Can Winship beat the odds of pancreatic cancer?

Investigators and clinicians are cracking the code in one of the deadliest cancers.

Photo by Jack Kearse

When Debra Bradley found out she had stage IV pancreatic cancer, she kept some of the information private. The diagnosis transformed her life. It spurred a marriage proposal and a promise that she would not need to face the grueling regimen of chemotherapy by herself. She kept working at her real estate job, with a determined attitude that carried over into how she approached her treatment. For most of 2016, Bradley and her new husband Gary Gross camped out in Winship's infusion center with their computers, taking care of business. "I was doing my job," she says. "That job was saving my life."

Bradley didn't reveal to acquaintances and work colleagues that she had pancreatic cancer, because of its formidable reputation. She didn't let most of her circle know until she rang the bell at Winship celebrating the end of her chemotherapy.

"People have this mindset about pancreatic cancer—it means you're on your way out," she says. "I didn't want people to feel sorry for me and get caught up in that. I did tell people that I would be away on some days for treatment."

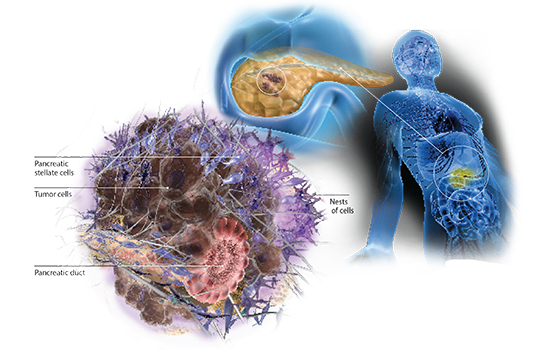

The pancreas, about six inches long, sits behind the stomach, surrounded by the small intestine, liver, gall bladder, and spleen. When it works properly, we don't think about it; when it's not working, people deal with chronic conditions such as diabetes, or life-threatening disease like pancreatic cancer. You can live without a gall bladder, but you can't live without a pancreas.

The pancreas houses cells that make insulin, critical to maintaining blood sugar levels, but most pancreatic cancers come from exocrine ductal cells, which make enzymes that help digest food.

Pancreatic cancer is intimidating. Around 20 percent of people survive a year after diagnosis, and less than 10 percent overall survive more than five years. Bassel El-Rayes, Winship's associate director for clinical research and director of the Winship Gastrointestinal Oncology Program, can list several reasons why.

It's stealthy—causing few overt symptoms at the beginning of the growth of a tumor, and metastasizing early. Surgery can be difficult, because tumors form close to critical blood vessels in the abdomen.

Pancreatic cancers use the local environment to their advantage, El-Rayes says. The cancer cells appear to recruit other cells from the body to form a protective shell, which keeps both the immune system and chemotherapy drugs out.

"If you look at a tumor from the pancreas, you will see small nests of cells embedded in scar tissue," he says. "The cancer uses this scar tissue as a shield, to its own advantage."

Breaking through the barrier

"They call her Wonder Woman," her husband Gary Gross says. "We felt lucky that she wasn't a surgical candidate. It's hard to know what made this happen. It could be the drug, it could be the exact makeup of the cancer, or it could be her disciplined approach."

When Bradley began her treatment regimen in April 2016, it included both standard chemotherapy and an experimental drug called BBI-608, as part of a phase Ib/II clinical trial. The drug was designed to target cancer stem cells, which are hardier cells, thought to survive chemotherapy and eventually come roaring back. She experienced an exceptional result.

"We've seen the spots on the liver disappear," El-Rayes said when Bradley completed her treatments in early 2017. "We still see a very tiny spot on the pancreas, which is hard to tell if it's a tumor or not. From a radiologic point, we don't see any evidence of disease."

Among the 66 patients in the BBI-608 study, the overall response rate was around 55 percent, according to results presented last summer at the World Congress on Gastrointestinal Cancer. That's almost double the response rate from previous studies that established the current standard of care. Bradley was one of just two "complete responders," rarely seen with pancreatic cancer. Since then, the BBI-608 plus chemotherapy study has expanded to a larger phase III trial.

When Bradley's story was told on local TV news, and then on NBC national news, dozens of people called Winship asking if they could be treated with the same drug combination. It was a clear indication that patients with pancreatic cancer are vigilantly looking for new treatments that raise the hope of survival.

Now, more than a year after finishing the combination therapy, Bradley continues to take BBI-608 daily without the chemotherapy. El-Rayes reports that Bradley still has no evidence of disease.

"They call her Wonder Woman," her husband Gary Gross says. "We felt lucky that she wasn't a surgical candidate. It's hard to know what made this happen. It could be the drug, it could be the exact makeup of the cancer, or it could be her disciplined approach."

In discussions with Bradley in 2016, El-Rayes advised that immunotherapy, which has transformed treatment of other types of cancer such as lung cancer and melanoma, was not likely to work by itself.

Immunotherapy agents like pembrolizumab and nivolumab get around a defense put up by many cancer cells that shuts off the immune system's ability to hunt them down. The drugs re-energize T cells that can then enter the tumor and destroy cancer cells. But so far, in clinical trials, they haven't been effective against pancreatic cancers when deployed by themselves.

Pancreatic cancers appear to have an extra layer of shielding. They work together with fibrotic cells called pancreatic stellate cells, which create those dense nests. For immunologists, their effects can be counterintuitive, because some of the molecules the stellate cells pump out, such as IL-6 (interleukin 6), are known to be markers of inflammation, says basic science researcher Gregory Lesinski.

Inflammation is a normal immune response when tissues are injured by bacteria, trauma, toxins, and other causes. It helps attract germ-fighting white blood cells, but if it persists—as happens with chronic infections and cancer—inflammation can actually undermine the immune system.

"Inflammation and a good immune response don't always go hand in hand," says El-Rayes. "High IL-6 causes immune exhaustion, and keeps the good cells out of the tumor."

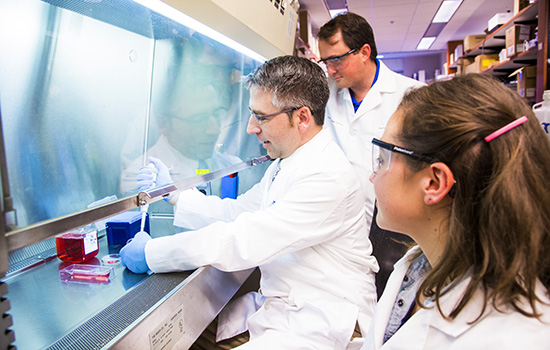

Gregory Lesinski with lab team members Matthew Farren and Hannah Komar.

Off-the-shelf options and new tactics

Now El-Rayes and Lesinski are teaming up to figure out how to successfully apply immunotherapy to pancreatic cancers. Lesinski had previously found that immune cells' activity predicts patient survival.

Based on his lab's recent success in animal models, Lesinski thinks that combining an immunotherapy drug with agents that stop IL-6 could pry open pancreatic cancers' protective shells. In those experiments, the combination resulted in fewer stellate cells and more T cells in the tumors. Fortunately, a couple of "off-the-shelf" options, drugs approved for rheumatoid arthritis, already exist for targeting IL-6, Lesinski says.

Already, El-Rayes and Lesinski are making use of another experimental drug called XL888. El-Rayes had begun to study a similar drug a few years before with colorectal cancer. Both inhibit a "chaperone" called HSP90, which escorts several growth-driving proteins after they are synthesized in cancer cells. El-Rayes had found that an HSP90 inhibitor was active against pancreatic cancer cells. Lesinski's lab also has been studying how to combine HSP90 inhibitors with other drugs to get a specific toxic effect against pancreatic cancer cells.

"We think that an HSP90 inhibitor could have both direct antitumor effects, and also alter stellate cell biology, which could let in the T cells," he says.

A clinical trial has begun at Winship combining XL888 with the immunotherapy drug pembrolizumab for advanced gastrointestinal cancers, including pancreatic cancer. With other forms of cancer, but not pancreatic cancer yet, a study of BBI-608, the drug that worked so well for Bradley, together with immunotherapy agents has started as well.

BBI-608 targets cancer stem cells and the immune system via inhibiting the molecule STAT3, part of the same pathway as IL-6, which Lesinski had identified as an ingredient of pancreatic cancer's fibrotic shield.

"It is likely that BBI-608's therapeutic effect came from its impact on stem cells, based on most of the published preclinical data," Lesinski says. "It is possible the drug may act in part by targeting other things STAT3 is involved in, but this is hard to prove in any individual patient."

Looking ahead, Winship researchers are considering more innovative approaches to getting through pancreatic cancer's defenses. One, proposed by translational scientist Lily Yang, consists of tiny particles that smuggle chemotherapy drugs such as doxorubicin or irinotecan into the tumor, guided by proteins abundant on pancreatic cancers. The particles' iron oxide core would allow radiologists to see where the particles are distributed in the body via magnetic resonance imaging. In recent preclinical experiments, the particles carry an enzyme that could help them chew up the fibrotic shield.

It is difficult to look at pancreatic cancer in a positive light, given its hydra-like nature. But Debra Bradley says that one consequence of her journey is a different view of challenges in her life.

"I'm not afraid of anything anymore," she says.

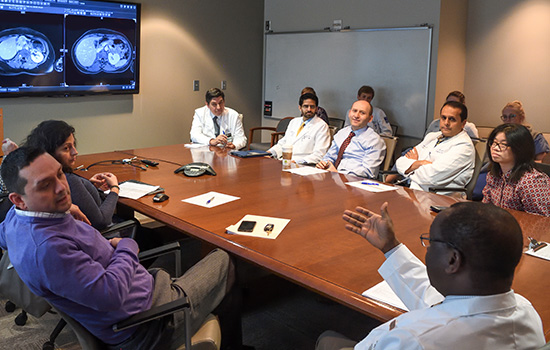

The multidisciplinary gastrointestinal tumor board meets weekly.

"This one will be tricky."

"That happens because of inflammation. It's a liver met [metastasis]."

You'd better know your abdominal anatomy if you come to a weekly meeting of the gastrointestinal (GI) tumor board at Winship Cancer Institute, because you will see the liver, pancreas, and other organs zooming by on the screen in a darkened conference room.

At one meeting, a resident scrolls rapidly through radiology images projected on the screen. Bassel El-Rayes is at the head of the table. The mood is serious, but not tense.

The discussion includes patients with colon or neuroendocrine cancers, but the largest number have pancreatic cancer. The group quickly gets to work reviewing patients of Juan Sarmiento, a specialist in surgery of the liver and pancreas.

"This is the hottest area, but this is not how a stage IV cancer behaves. There is no other disease," El-Rayes says.

"Clinically and biologically, this guy is doing well; he's motivated," Sarmiento says.

For another patient, the tumor appears to be close to the portal vein, which drains the liver. The patient has been on a chemotherapy combination. The group discusses whether stereotactic body radiation therapy would be a good alternative to surgery.

For a third, Sarmiento asks an interventional radiologist about directed radiation. "Is that too close to the diaphragm?" he asks. "There may be more pain associated with the procedure," is the reply.

Each week, the tumor board reviews about 20 cases. After the meeting, the primary physician goes back and communicates the tumor board recommendation to the patient, and a nurse navigator helps make appointments for additional therapies if needed. A multidisciplinary tumor board provides a personalized treatment plan for each patient, including the appropriate use and timing of multiple therapies. This way, the patient benefits from the collective expertise of the team.