Vaping: Friend or Foe of Public Health?

Emory researchers, led by Winship's Carla Berg, work to stem the flow of marketing e-cigarettes to young people.

Todd Gano smoked two packs of cigarettes a day for 30 years. He tried everything to quit: the patch, gum, Chantix, acupuncture, and hypnosis. Nothing worked. Then about 10 years ago, he heard about a device, only available in China, that let you inhale nicotine vapor without smoking a cigarette.

"I got my kit from China, started vaping, and I quit smoking that day," Gano says.

When the devices – now widely known as e-cigarettes, vapes, or vape pens – hit the United States, Gano wanted to make the technology available to others desperate to quit smoking cigarettes. Today, the Atlanta businessman owns and operates VapeRite, which includes an online retailer, four brick and mortar vape shops, and VR Labs, a manufacturer and wholesaler of the nicotine-infused liquids or "e-juices" vaporized by the devices.

Public health experts have watched the growth of the U.S. vape industry with skepticism, unsure if the tobacco alternatives are friend or foe. While the products may reduce harm for smokers, they offer no benefits to the scores of young non-smokers who have gotten their hands on them. The VAPES Study (Vape shop Advertising, Place characteristics & Effects Surveillance), led by Carla Berg, associate director for Population Sciences at Winship, is following the market closely to understand the role retailers play in getting the products into the hands and lungs of young people.

"How do you brand and market a product so it only appeals to a population that could potentially benefit from it - smokers - without marketing it to a population - youth - that will absolutely not get any benefit from it? That's the question," says Berg.

In the shadow of a predatory industry

The tobacco industry is known for capturing and keeping young customers. "Over the years, and throughout different regulatory contexts, they have always managed to engage young people in their products," says Berg, “And if there's anything the tobacco industry knows how to do, it’s how to keep their customers." Berg's research seeks to determine whether the vape industry is taking a similar tack.

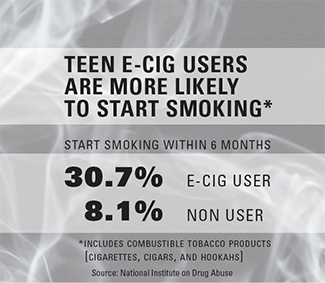

E-cigarettes may be a potential pathway for smokers to quit, but for young people, that path moves in the opposite direction. Middle- and high-schoolers are up to three times as likely to vape as they are to smoke. Yet, once they start vaping, nearly one in three will start smoking in the next six months. Compare that to just one in 12 non-vaping teens who will become a smoker in the next six months.

More than 3.6 million middle- and high-schoolers vape. Nakiema Wallace's 13-year-old son is one of them. The Atlanta mother of three was shocked when she found her son's vape pen in the dryer. "He's only in middle school. I just didn't think we were there yet." One look at her son's social media history showed just how prevalent vaping is among middle-schoolers. "Six or seven boys had been doing it with him."

Shining light on gray areas

Berg and her colleagues want to learn what retail behaviors are helping get these products into children’s hands. "Tobacco retailers have historically placed themselves in communities of low socioeconomic status with a high proportion of minorities and young people," Berg says. "Whether the vape shop industry is doing the same thing is still a question."

Berg's research team visited 180 retailers, including convenience stores and dedicated vape shops, in Atlanta, Boston, Minneapolis, Oklahoma City, San Diego, and Seattle. The researchers are examining the extent to which young people are the targets of e-cigarette sales and advertising and what's happening at the point of sale that might discourage or encourage young people to take up the habit.

The team also aims to uncover innovative ways in which retailers might get around regulations, such as the federal ban that prohibits retailers from offering free samples. "To circumvent that, they'll charge a 'membership' fee of a dollar a year, which buys you as many samples as you'd like, or you can put a quarter on the bar and sample for the next two hours," Berg says.

The team's findings could help inform FDA regulations intended to restrict youth access to the products.

Friends and foes

It's too soon to tell what lessons public health officials and regulatory agencies will learn from the VAPES Study, which will continue through 2022. But there's one thing Berg is sure of: the point isn't to get rid of e-cigarettes altogether.

"A lot of smokers are saying they benefit from them, so we don't want to throw the baby out with the bathwater," Berg says, "but there’s a huge concern about the public health impact."

What's more, she adds, the vape industry is made up of both friends and foes of public health. In their visits to vape retailers around the country, the research team has found retailers that operate ethically with a mission to support smoking cessation. Gano's VapeRite, she says, is one of them.

"We check every single ID. I don't care if you're 18 or 80, or if you come in here every week," Gano says. "And if you aren't already a smoker, we're going to say 'This is really for people who smoke - to get them off of cigarettes. Are you sure you want to get into this?'"