Zack Usilton Looks to the Future

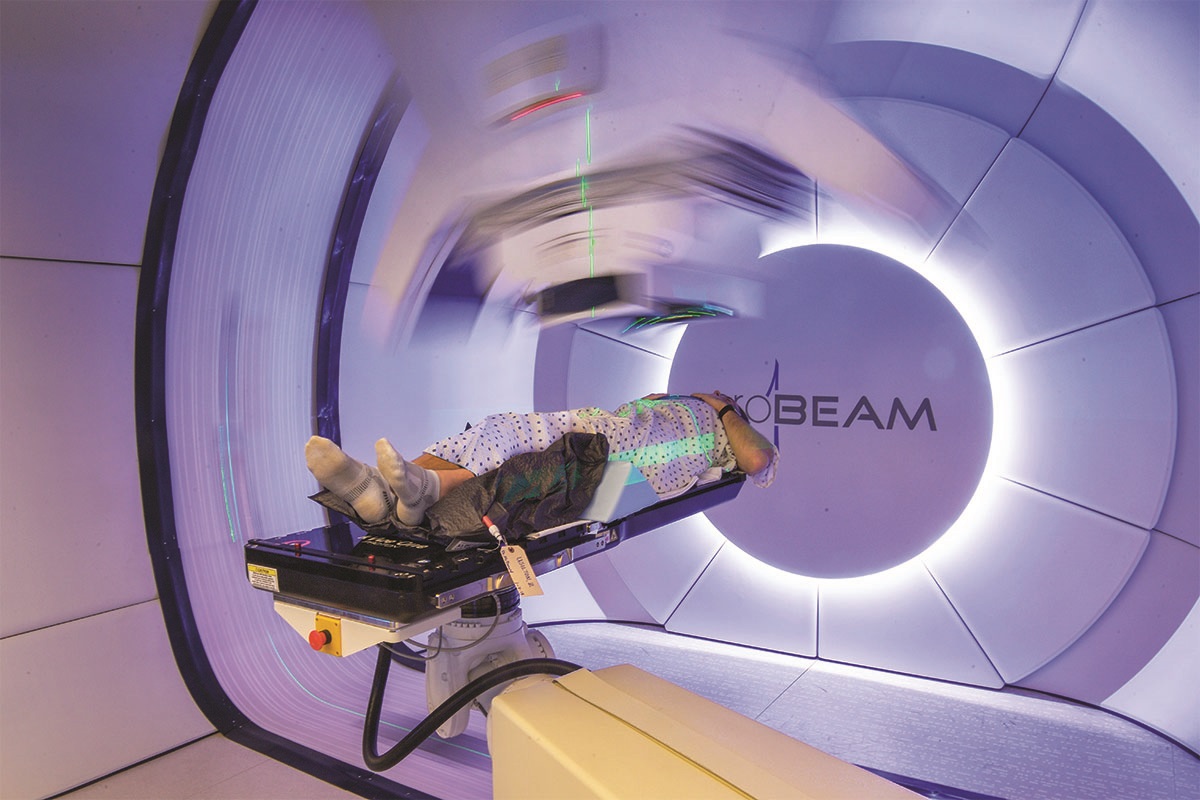

One of the first patients treated at the Emory Proton Therapy Center.

Photography by Jack Kearse

When Zack Usilton learned, at age 25, that he had a tumor tangled up in the nerves at the base of his spine, his choice was clear. He would have surgery regardless of the risks. "The doctor said there were thousands of nerve [linings] back there and that no one knows what they go to," Usilton recalls. "I did it knowing that it might damage my ability to walk, to feel my fingertips, or anything else, and there was the chance that they wouldn't scrape away every last tumor particle. I guess in a way, I played the odds."

Back then, the Atlanta native only had himself to worry about. Playing the odds was his prerogative. Ten years later, when the tumor came back, Usilton had a wife, a daughter, a new house under construction, and another child on the way. And he wasn't crazy about either of his options: another chancy surgery or radiation. The former brought with it all the same risks as the first time, including months of recovery and potential loss of bladder or bowel function, and the latter upped his odds of more cancer later in life.

"I didn't want to take the risk of a second surgery, but I had major concerns about radiation and its long-term effects," Usilton says.

Zack and Anne Usilton, pictured here with 2-year old Caroline.

"Proton therapy is about reducing unnecessary radiation in cases where we can reduce or avoid some of the side effects and risks of therapy," says Mark McDonald, medical director of the Emory Proton Therapy Center, who described Usilton as a perfect candidate for such treatment. "Someone who is young like Zack stands to benefit greatly from proton therapy by reducing the risks of longterm consequences of therapy, and in his case we were also able to avoid any nausea or diarrhea during treatment by avoiding delivery of any radiation to the intestines."

Usilton was one of the first patients at the new center. The treatments, every weekday for six weeks, took less than one hour of his day. As for options that would bring Usilton the greatest odds of a long life with his wife and children, he says, "proton therapy was my best bet."

The Power of The Room

Within five minutes of his arrival at the Emory Proton Therapy Center every day, Usilton was escorted back for the painless procedure. He was glad that the treatment room was a wide-open area that patients walk right into, a far cry from the claustrophobic conditions of an MRI machine.

"It's something out of a movie. When you walk in, you can feel the power of the room."

Protons themselves strike a tumor more precisely than traditional radiation, and the experience as a whole was customized precisely for Usilton. Before his first session, staff custom molded a cushion under Usilton's head and legs to help position him on the table and make it as comfortable as possible. During treatment sessions, which lasted only a few minutes, staff played Usilton's music picks.

"You're comfortable. You're greeted by friendly faces," he says. "They slide me under the machine and then – I don't even know that the treatment has happened – they say, 'All right, time to go.'"

Proton therapy didn't cause any serious side effects for Usilton, although he did experience fatigue. "The minute I put my daughter down at night, I crash pretty quickly. If the worst thing that happens is going to bed at eight rather than 10 or 11, that's pretty good."

That's a relief for Usilton's wife Anne, too. She says the thought of another surgery was scarier to her than the cancer itself. She was friends with Usilton when he had surgery 10 years ago and still remembers it. "It was so debilitating; I just didn't want to see him in pain again."

She saw no pain at her husband's last treatment in March. "It's easy to see that everyone loves what they do. They're very passionate about it. That makes the whole process easier, especially for people in far more difficult situations than Zack's."

Looking Ahead

The tumor at the base of Usilton's spine will not simply melt away. That's the nature of the tumor, not the treatment. But proton therapy could prevent it from ever growing again. Usilton and his doctors will watch it through follow-up MRIs – just as they have done for the last 10 years.

Usilton goes in for his first post-treatment scan in May. But those results will surely be upstaged by some other news expected that month. "We don't know whether it's a boy or a girl," Usilton says. “It's a ton of fun to be surprised. I'll be the first to know."