Keith Sievers Finds His "Warrior Mode"

Small victories are key to staying strong during long treatments

It started with a spot on his forehead in January 2020. Turned out it was a type of skin cancer, squamous cell carcinoma. As the COVID-19 pandemic got under way that winter and spring, Keith Sievers was receiving radiation treatment.

Six months into his treatment, though, Sievers noticed a lump in his neck. That’s when an ear, nose and throat surgeon at a local community hospital, where he was being treated, recommended he pursue the surgery he needed at Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University.

The surgeon said the procedure would be “delicate” because of its proximity to the nerves and major arteries that pass through the neck. “You need a surgeon who does this all day, every day,” Sievers recalls him as saying. “I could certainly operate on you, but you need to be at Winship.”

Sievers credits that surgeon’s referral to Winship as “the” key contribution toward saving his life.

Meeting, and joining, the care team

Like other new Winship patients, Sievers—together with his wife, Robin Sievers—came in to meet the Winship team who would be caring for him.

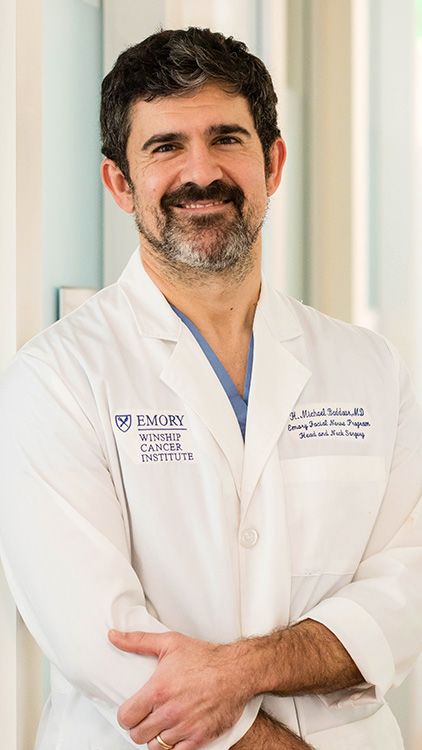

The surgery would be performed by H. Michael Baddour, Jr., MD, an expert in head and neck surgical oncology and complex microvascular reconstruction at Winship, and associate professor in the Department of Otolaryngology at Emory University School of Medicine.

His team also included Soumon Rudra, MD, a Winship researcher and radiation oncologist specializing in the treatment of head and neck cancer and gastrointestinal cancer, and assistant professor at Emory University School of Medicine.

His medical oncologist was Nabil F. Saba, MD, FACP, director of Head and Neck Oncology and the Lynne and Howard Halpern Chair in Head and Neck Cancer Research at Winship and professor at Emory University School of Medicine.

You have to trust your doctors. You have to stay with them. You have to take their advice. It’s important that you really understand the options

and the treatments. Don’t be afraid to ask questions.

The daylong visit also included meetings with a dental oncologist, pharmacologist, speech therapist and even a swallowing therapist.

Baddour emphasizes that Sievers himself—and each one of his other patients—is “the primary person on the team.” He explains, “They are the ultimate decision-makers driving their own care. And I feel like the only way they can make a decision is if they have all the information.”

Saba says, “Having patients actively participate in the decision-making is important to navigate the complex treatment programs.” He adds, “I think trust is a key ingredient of success.”

Sievers agrees. “You have to trust your doctors,” he says. “You have to stay with them. You have to take their advice. It’s important that you really understand the options and the treatments. Don’t be afraid to ask questions.”

Most important of all, says Sievers, is to recognize in the partnership “how hard these people are working, and how difficult their jobs are. You really have to show them that you respect what they’re doing, and that you appreciate them.”

Sievers’ team recommended the surgery. He had the surgery within a couple of weeks, followed by proton radiation therapy.

They are the ultimate decision-makers driving their own care. And I feel like the only way they can make a decision is if they have all the information.

Complicating an already difficult experience, Sievers’ personal drama played out against the backdrop of the growing COVID-19 pandemic. Loved ones were routinely barred from visiting family members or friends in hospitals because of the rampant fear of contagion. “I had to drop him off at the curb for the surgery,” Robin Sievers recalls. “I couldn't go in the hospital, and that was hard for both of us.”

By the end of his second year with cancer—which had included surgery, proton therapy and recovery—Sievers was receiving scans every three months. That’s how he found out the cancer had spread into his lung. “It was a fairly significant tumor,” he says with understatement.

H. Michael Baddour, Jr., MD, head and neck surgeon

H. Michael Baddour, Jr., MD, head and neck surgeon

Soumon Rudra, MD, radiation oncologist

Soumon Rudra, MD, radiation oncologist

Nabil F. Saba, MD, medical oncologist

Nabil F. Saba, MD, medical oncologist

Deciding to “leave it in”

Both Sievers met with Saba. This time Saba explained that going after the tumor with radiotherapy may not be sufficient to achieve long-term control; “zapping it” couldn’t guarantee Keith’s survival when the cancer already had recurred before. He recalls Saba as saying, “Look, it’s spread three times. We need to be concerned about the bigger picture.”

After discussing traditional treatments as well as potential treatments being tested in clinical trials, “We elected to go with the trial,” says Sievers.

As it happens, the choice to participate in the clinical trial was an auspicious one.

“At the end of five months,” says Sievers, “the tumor was gone, a complete response.” He adds, “And, knock on wood, I’ve been clean ever since.”

Getting to this point was not easy. Every two weeks, the Sievers made the 70-mile drive each way from their home in the north Georgia mountains to Atlanta, so Keith could receive what he calls “a miracle drug” because of how he says it “really stamped out the cancer.” The drug was an immunotherapy drug being tested in the trial with or without another agent called cetuximab.

At the end of five months, the tumor was gone, a complete response. And, knock on wood, I’ve been clean ever since.

As of the time of our interview, in December 2023, Sievers returns to Winship every three months for a set of scans, and every six weeks to have the port flushed. He doesn’t even have to take maintenance medication.

"Warrior mode"

Rudra, like Sievers’ other care team members, marvels at Sievers’ active participation in his own care.

“I just want to note,” Rudra says, “how thoughtful and considerate Keith was in his decision to enroll in a clinical trial.” He points out that enrolling in a clinical trial doesn’t guarantee a good outcome. “Yet Keith did it because he thought he could help future patients.” He adds, “Keith

and Robin spent significant amounts of time traveling and answering extra questions about his treatments due to his clinical trial participation.”

For Keith Sievers, with Robin at his side the entire time, the sacrifice of time and effort seemed like nothing when compared to the potential payoff: improving his own health and contributing to the advancement of research that could benefit others. It was a natural outgrowth of the couple’s operating philosophy.

Keith explained that after his initial diagnosis, he found three things to be the most challenging to deal with. First, he says, is facing your mortality. “You always are aware of it, but you really have to look it in the eye, and that just takes some time to let it settle in.”

Then there is the fear of the unknown, about “what’s going to happen next,” and a lot of uncertainty.

Finally, there is the waiting—for appointments, for procedures, for results. Every step takes time.

“Once you get through the uncertainty,” Sievers says, “and once you get into the battle and you’re doing something about it, you really feel like now

you’ve got some control—and that’s really helpful for people.”

"Winning the war"

He had to push past claustrophobia to be able to remain strapped to a table for 45 minutes—with a full facial mask covering his face—to receive proton therapy on his neck. “I took pride in that,” he says.

“Winning those little victories is uplifting to people,” Sievers says. “If you look at it like a fight, and you look at it like, ‘I may lose a battle or two along the way, but I’m going to win this war’ and you really focus on winning the battles, that really is uplifting and helps to win the war.”

Support Head and Neck Cancer Research

Keith Sievers chose to treat his cancer by enrolling in a clinical trial. He was not only hoping for a good outcome for his own health but was looking to help advance the research that would help patients in the future.

Make a gift to the Head and Neck Cancer Research Fund to support much-needed clinical trials that will help change the lives of future patients.

Give now to fund the equipment, imaging, radiology and technologies that help Winship Cancer Institute provide world-class cancer care every day.

More from Winship Cancer Institute

Treating a Complex Cancer Requires a Multidisciplinary Team

Winship's expertise and personalized care helped Trina navigate a detailed treatment plan for her head and neck cancer, emphasizing comprehensive services and a dedicated team. But Trina was most impressed by her team’s ability to connect with her as a person.

Head and Neck Cancer Care at Winship

When you come to Winship Cancer Institute at Emory Midtown for head and neck cancer care, you have a comprehensive team of experts dedicated to your well-being.

Winship Magazine Spring 2024

The Spring 2024 issue of Winship Magazine features how artificial intelligence is changing cancer medicine, highlights a patient story of Keith finding his "warrior mode" , and describes how Winship is contributing to the Cancer Moonshot initiative, and much more.

Did you like this article? Read more features in Winship Magazine.