Turning the Tide

cover story

Winship leads the way in multiple myeloma advances

When executive assistant Danielle Spann began feeling severe pain in her lower back and hips, she assumed it was just the price of getting in shape. “I was working out a great deal at the time,” she says. She did what most of us would do: tried to ignore it.

Two months passed, but the pain didn’t subside. She visited an orthopedist, who ordered X-rays. The images revealed a mass on her spine, and the orthopedist referred her to Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University.

After a series of tests, Spann learned she had multiple myeloma, a blood cancer that develops in plasma cells within the bone marrow. She would need chemotherapy, a stem cell transplant and other medications. Even with treatment, her prognosis was grim: doctors told her she had about five years to live.

“That was in 2011,” Spann says. “And here I am now.”

The story of multiple myeloma treatment at Winship is one of perseverance and partnerships. Advances made by the Winship myeloma team should bring hope to anyone diagnosed with —or living with—the condition today. Over the past two decades, these physicians and researchers have helped transform multiple myeloma from a death sentence into a manageable condition. More patients are living well past their initial prognosis—and not just surviving but thriving.

“I’m doing anything and everything I can to stay on this earth as long as possible,” Spann says. “Where I am today, it’s because of Emory. It’s because of my Winship doctors.”

When executive assistant Danielle Spann began feeling severe pain in her lower back and hips, she assumed it was just the price of getting in shape. “I was working out a great deal at the time,” she says. She did what most of us would do: tried to ignore it.

Two months passed, but the pain didn’t subside. She visited an orthopedist, who ordered X-rays. The images revealed a mass on her spine, and the orthopedist referred her to Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University.

After a series of tests, Spann learned she had multiple myeloma, a blood cancer that develops in plasma cells within the bone marrow. She would need chemotherapy, a stem cell transplant and other medications. Even with treatment, her prognosis was grim: doctors told her she had about five years to live.

“That was in 2011,” Spann says. “And here I am now.”

The story of multiple myeloma treatment at Winship is one of perseverance and partnerships. Advances made by the Winship myeloma team should bring hope to anyone diagnosed with —or living with—the condition today. Over the past two decades, these physicians and researchers have helped transform multiple myeloma from a death sentence into a manageable condition. More patients are living well past their initial prognosis—and not just surviving but thriving.

“I’m doing anything and everything I can to stay on this earth as long as possible,” Spann says. “Where I am today, it’s because of Emory. It’s because of my Winship doctors.”

“This too shall pass”

Spann’s 15-year cancer experience offers a window into the challenges many multiple myeloma patients face. Soon after her diagnosis, she sneezed and fractured a vertebra, necessitating emergency surgery. “That’s how weak the myeloma had made my bones,” she says. She began receiving chemotherapy and steroids on an innovative clinical trial, but the disease progressed despite using modern drugs. She needed an autologous stem cell transplant, where her own stem cells were harvested before chemotherapy, frozen and then infused back into her body after chemotherapy—an arduous process that required a 28-day hospital stay.

Although she felt better afterward, her myeloma numbers had not improved as much as her doctors had hoped. Doctors told her she needed a second, “tandem,” stem cell transplant. Spann returned to the hospital for another 15 days.

Everything about that second transplant was grueling, she recalls. “I kept telling myself, ‘This too shall pass,’” Spann says. She vomited almost constantly—she couldn’t hear the food cart rolling down the hospital hallway without becoming nauseated. She developed a skin reaction that made receiving visitors difficult. “This too shall pass” has since become her life motto. “Whatever it is, whatever the difficulty, it’s temporary,” she says. “How I’m feeling right now, it’s not going to be forever.”

Take what Spann was experiencing and multiply it by 700 to 800 people: That’s how many new cases of multiple myeloma Winship’s myeloma clinic sees each year.

Multiple myeloma disproportionately affects Black people—30% to 40% of Winship’s patients with multiple myeloma are Black—and they have approximately twice the incidence and mortality rates as white people. Since Winship serves a large African American population, the myeloma team manages one of the largest caseloads in the country.

“From the 1970s through the early 2000s, survival rates were just three years on average for these patients,” says Ajay K. Nooka, Winship’s associate director of clinical research and director of the Myeloma Program in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine. “We needed to do something different. We needed to rethink almost everything.”

Danielle Spann

Danielle Spann

Spann’s 15-year cancer experience offers a window into the challenges many multiple myeloma patients face. Soon after her diagnosis, she sneezed and fractured a vertebra, necessitating emergency surgery. “That’s how weak the myeloma had made my bones,” she says. She began receiving chemotherapy and steroids on an innovative clinical trial, but the disease progressed despite using modern drugs. She needed an autologous stem cell transplant, where her own stem cells were harvested before chemotherapy, frozen and then infused back into her body after chemotherapy—an arduous process that required a 28-day hospital stay.

Although she felt better afterward, her myeloma numbers had not improved as much as her doctors had hoped. Doctors told her she needed a second, “tandem,” stem cell transplant. Spann returned to the hospital for another 15 days.

Everything about that second transplant was grueling, she recalls. “I kept telling myself, ‘This too shall pass,’” Spann says. She vomited almost constantly—she couldn’t hear the food cart rolling down the hospital hallway without becoming nauseated. She developed a skin reaction that made receiving visitors difficult. “This too shall pass” has since become her life motto. “Whatever it is, whatever the difficulty, it’s temporary,” she says. “How I’m feeling right now, it’s not going to be forever.”

Take what Spann was experiencing and multiply it by 700 to 800 people: That’s how many new cases of multiple myeloma Winship’s myeloma clinic sees each year.

Multiple myeloma disproportionately affects Black people—30% to 40% of Winship’s patients with multiple myeloma are Black—and they have approximately twice the incidence and mortality rates as white people. Since Winship serves a large African American population, the myeloma team manages one of the largest caseloads in the country.

“From the 1970s through the early 2000s, survival rates were just three years on average for these patients,” says Ajay K. Nooka, Winship’s associate director of clinical research and director of the Myeloma Program in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine. “We needed to do something different. We needed to rethink almost everything.”

A five-year plan

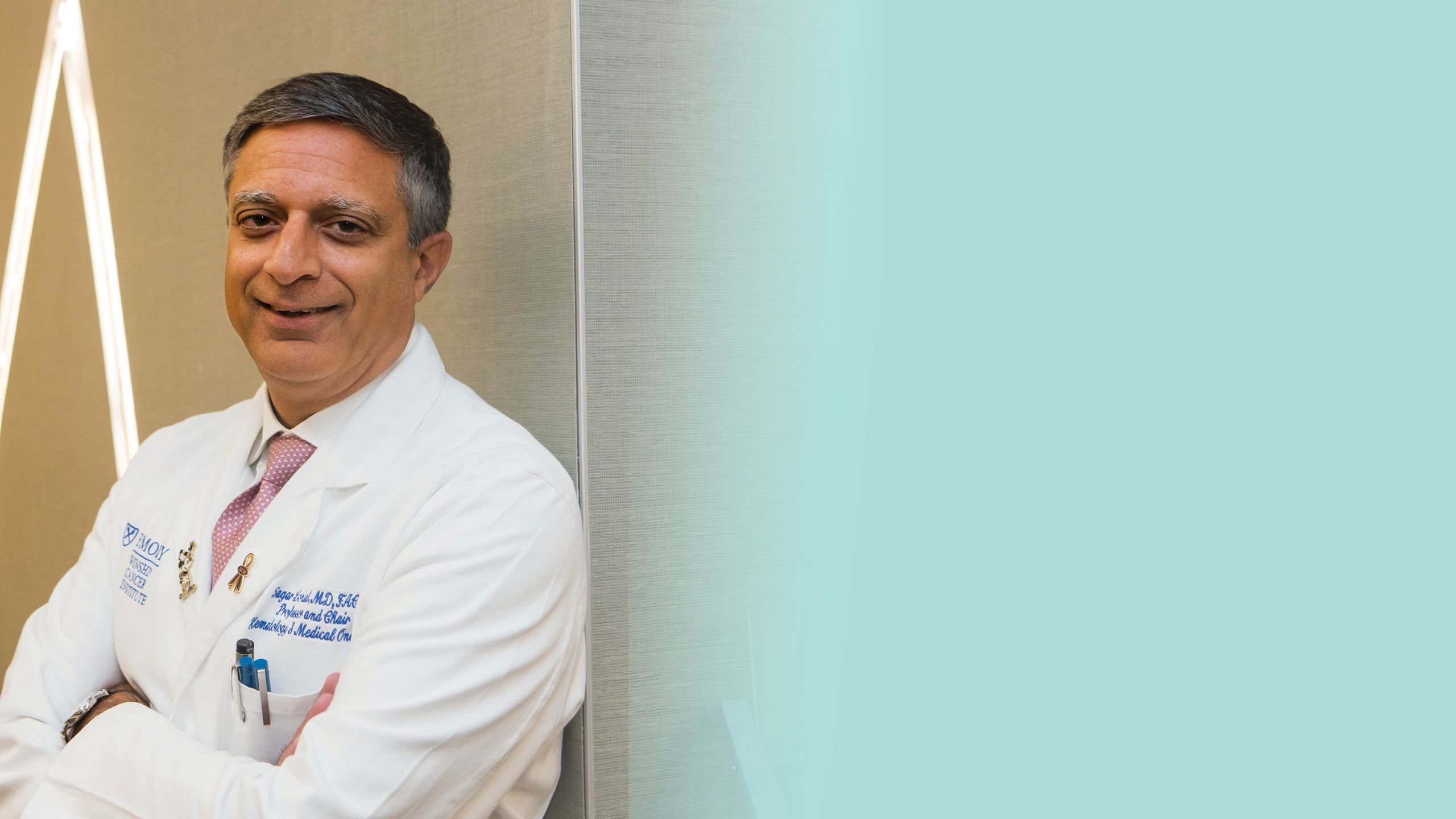

Sagar Lonial is Winship’s chief medical officer, the Anne and Bernard Gray Family Chair in Cancer and professor and chair in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine. Together with Nooka and other Winship physicians and researchers, Lonial spearheaded a comprehensive initiative to help prolong the lives of patients with multiple myeloma. Early on, the team had one overarching objective: Get out in front of the cancer.

“We didn’t want to try a treatment and then just wait to see what happened,” Lonial says. “We needed a long-term plan: treatment regimens that would maximize how long the disease could be controlled or remain in remission. We had to start thinking five or 10 years ahead for each patient. That was the way to stay ahead of this cancer.”

Two new medications tested in clinical trials at Winship helped make this planning more than a pipe dream: bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor introduced in 2003, and lenalidomide, an immune modulating drug introduced three years later, in 2006.

Patients saw marked improvements when these new therapies were deployed as combination treatments along with a steroid. Even those with relapsing or refractory multiple myeloma, which is notoriously difficult to treat, responded positively. “We were one of the pioneers here,” Nooka says. “Winship started offering these drugs to patients very early as frontline treatments.”

Sagar Lonial

Sagar Lonial

Sagar Lonial is Winship’s chief medical officer, the Anne and Bernard Gray Family Chair in Cancer and professor and chair in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine. Together with Nooka and other Winship physicians and researchers, Lonial spearheaded a comprehensive initiative to help prolong the lives of patients with multiple myeloma. Early on, the team had one overarching objective: Get out in front of the cancer.

“We didn’t want to try a treatment and then just wait to see what happened,” Lonial says. “We needed a long-term plan: treatment regimens that would maximize how long the disease could be controlled or remain in remission. We had to start thinking five or 10 years ahead for each patient. That was the way to stay ahead of this cancer.”

Two new medications tested in clinical trials at Winship helped make this planning more than a pipe dream: bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor introduced in 2003, and lenalidomide, an immune modulating drug introduced three years later, in 2006.

Patients saw marked improvements when these new therapies were deployed as combination treatments along with a steroid. Even those with relapsing or refractory multiple myeloma, which is notoriously difficult to treat, responded positively. “We were one of the pioneers here,” Nooka says. “Winship started offering these drugs to patients very early as frontline treatments.”

Combinations are the key

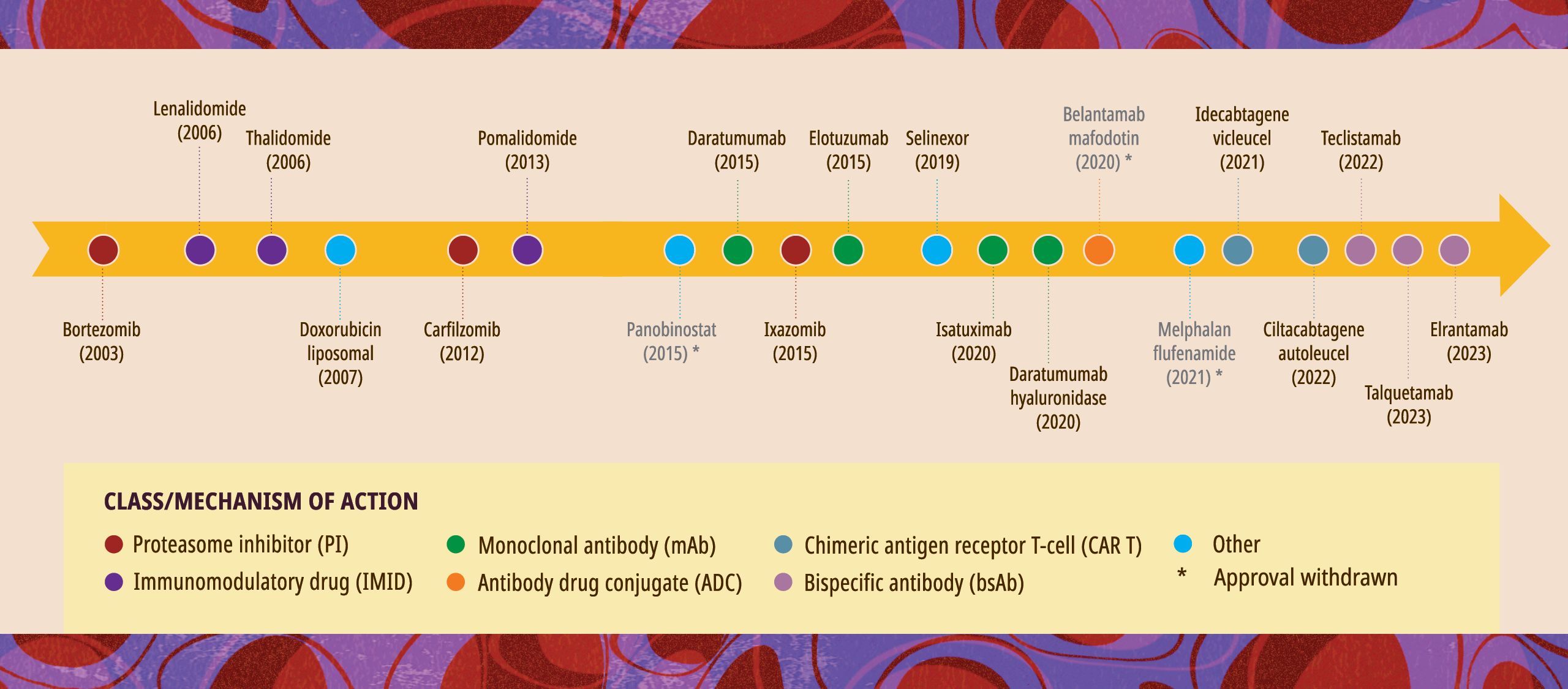

Since then, the number of new medications for multiple myeloma has risen sharply, from just two in 2006 to 13 and counting today. Every single myeloma drug approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the last two decades has been tested in clinical trials at Winship. And it’s not just the individual drug that matters: it’s their combination.

“Combination therapy is key,” says Lonial. “It allows us to hit the disease from multiple different angles.” Using a single medication until it no longer works isn’t helpful. “That approach just induces drug resistance,” he says.

To combat this challenge, the Winship team has tested a variety of combination strategies to put the disease into remission, and developed lower-intensity treatments that can serve as maintenance therapy for the long term.

Following her tandem stem cell transplant, Spann started on one of those combination treatments, a drug cocktail that, in her words, “kept my numbers down until it didn’t.” Her myeloma was particularly aggressive, and her Winship physicians tried several combinations over the next few years, seeking the mix that would send the cancer into remission. Some of the medications she received came through Winship’s clinical trials. Spann remembers one treatment working so well, and for so long, that she received permission to stay on it after the study ended. “That formula worked for me for a long time,” she says.

Today, the latest therapeutic options for multiple myeloma include bispecific antibodies, which bridge tumor and immune cells to help recruit the patient’s immune system to fight the cancer, and CAR T-cell therapy, which engineers the patient’s T cells, a type of white blood cell, to recognize and attack myeloma cells. They potentially help to achieve and extend deep remission of the disease over longer periods. The myeloma team at Winship has helped lead both developments, offering a clinical trial of a bispecific antibody during the COVID-19 pandemic and conducting close to 100 CAR T-cell procedures in Winship patients just in the last year.

Those living with a multiple myeloma diagnosis are eager for what’s coming down the research pipeline. “In some health care settings, people are skeptical about clinical trials,” Nooka says. “But our patients are asking to join these studies. In a trial of this kind, there are no sugar pills; you’re either getting the regular standard of care or the new treatment. There’s no downside. Patients want to be part of it.”

Since then, the number of new medications for multiple myeloma has risen sharply, from just two in 2006 to 13 and counting today. Every single myeloma drug approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the last two decades has been tested in clinical trials at Winship. And it’s not just the individual drug that matters: it’s their combination.

“Combination therapy is key,” says Lonial. “It allows us to hit the disease from multiple different angles.” Using a single medication until it no longer works isn’t helpful. “That approach just induces drug resistance,” he says. To combat this challenge, the Winship team has tested a variety of combination strategies to put the disease into remission, and developed lower-intensity treatments that can serve as maintenance therapy for the long term.

Following her tandem stem cell transplant, Spann started on one of those combination treatments, a drug cocktail that, in her words, “kept my numbers down until it didn’t.” Her myeloma was particularly aggressive, and her Winship physicians tried several combinations over the next few years, seeking the mix that would send the cancer into remission. Some of the medications she received came through Winship’s clinical trials. Spann remembers one treatment working so well, and for so long, that she received permission to stay on it after the study ended. “That formula worked for me for a long time,” she says.

Today, the latest therapeutic options for multiple myeloma include bispecific antibodies, which bridge tumor and immune cells to help recruit the patient’s immune system to fight the cancer, and CAR T-cell therapy, which engineers the patient’s T cells, a type of white blood cell, to recognize and attack myeloma cells. They potentially help to achieve and extend deep remission of the disease over longer periods. The myeloma team at Winship has helped lead both developments, offering a clinical trial of a bispecific antibody during the COVID-19 pandemic and conducting close to 100 CAR T-cell procedures in Winship patients just in the last year.

Those living with a multiple myeloma diagnosis are eager for what’s coming down the research pipeline. “In some health care settings, people are skeptical about clinical trials,” Nooka says. “But our patients are asking to join these studies. In a trial of this kind, there are no sugar pills; you’re either getting the regular standard of care or the new treatment. There’s no downside. Patients want to be part of it.”

A timeline of U.S. Food and Drug Administration multiple myeloma drug approvals/withdrawals from 2003-2023

Prevention and cure

With research momentum on their side, Winship investigators are turning to two new frontiers in the progress against multiple myeloma: prevention and cure.

Smoldering myeloma is a precursor condition that leads to multiple myeloma in 10% to 15% of those diagnosed. The condition doesn’t cause noticeable symptoms and is often caught only after an abnormality shows up in routine bloodwork. In the past, physicians didn’t treat smoldering myeloma; they simply monitored the patient to see if cancer developed. Now, however, they’re preparing to intervene earlier. If clinicians can intercept the disease during this “smoldering” stage, they could prevent multiple myeloma from ever developing.

“If you intervene early enough and prevent the organ damage, the fractures and the kidney failure that multiple myeloma can cause, that’s a huge win for patients,” Lonial says.

For those who have been living with this cancer for 10 or 15 years, another transformation could be on the horizon: stopping treatment altogether. The new classes of drugs are so effective at controlling multiple myeloma that Winship researchers are now talking about the prospect of ending maintenance therapy for some people—though they caution that such discussion is still very preliminary.

“One of the longstanding tenets of therapy in myeloma is the principle of continuous or maintenance treatment,” says Lonial. “Until now, patients have always been on some sort of low-dose therapy, even when they’re in remission.” Think of it like taking medication for high blood pressure: Your blood pressure might drop to normal levels, but that’s because you’re taking the drug, so you stay on it. A similar assumption has guided the treatment of multiple myeloma—until very recently.

Today, Winship investigators are working to combine multiple immune therapies, deliver them to the patient over a short period of time, stop the cancer in its tracks—and then stop treatment. Lonial and his colleagues are in the early stages of concept development for a possible clinical trial exploring this potential “cure.”

Even five years ago, such talk might have been considered far-fetched. Not anymore.

“There’s a possibility that some patients could come off these drugs and not need to stay on them forever,” says Nooka.

Ajay K. Nooka

Ajay K. Nooka

With research momentum on their side, Winship investigators are turning to two new frontiers in the progress against multiple myeloma: prevention and cure.

Smoldering myeloma is a precursor condition that leads to multiple myeloma in 10% to 15% of those diagnosed. The condition doesn’t cause noticeable symptoms and is often caught only after an abnormality shows up in routine bloodwork. In the past, physicians didn’t treat smoldering myeloma; they simply monitored the patient to see if cancer developed. Now, however, they’re preparing to intervene earlier. If clinicians can intercept the disease during this “smoldering” stage, they could prevent multiple myeloma from ever developing.

“If you intervene early enough and prevent the organ damage, the fractures and the kidney failure that multiple myeloma can cause, that’s a huge win for patients,” Lonial says.

For those who have been living with this cancer for 10 or 15 years, another transformation could be on the horizon: stopping treatment altogether. The new classes of drugs are so effective at controlling multiple myeloma that Winship researchers are now talking about the prospect of ending maintenance therapy for some people—though they caution that such discussion is still very preliminary.

“One of the longstanding tenets of therapy in myeloma is the principle of continuous or maintenance treatment,” says Lonial. “Until now, patients have always been on some sort of low-dose therapy, even when they’re in remission.” Think of it like taking medication for high blood pressure: Your blood pressure might drop to normal levels, but that’s because you’re taking the drug, so you stay on it. A similar assumption has guided the treatment of multiple myeloma—until very recently.

Today, Winship investigators are working to combine multiple immune therapies, deliver them to the patient over a short period of time, stop the cancer in its tracks—and then stop treatment. Lonial and his colleagues are in the early stages of concept development for a possible clinical trial exploring this potential “cure.”

Even five years ago, such talk might have been considered far-fetched. Not anymore.

“There’s a possibility that some patients could come off these drugs and not need to stay on them forever,” says Nooka.

The power of partnerships

As for Spann, she’s on another combination regimen these days, and it’s working. When she had her bloodwork done this past summer, she was declared to have a “confirmed complete response”—no myeloma cells detected in her urine, bone marrow or blood. She still comes in once a month for treatment, but she has also started volunteering at the clinic, talking with patients newly diagnosed with myeloma and offering encouragement. “I’m not the first person, nor will I be the last, to have a multiple myeloma diagnosis,” she says. “I want to let others know they’re not alone, and there’s hope.”

Winship now has close to 5,000 patients in the myeloma clinic—and counting. The increased numbers are because those diagnosed are living so much longer. That expanding timeframe fosters strong bonds between a patient and their care team. “Dr. Nooka is like family

to me,” Spann says.

Lonial recently took training fellows on rounds through the clinic. In a single day, they saw a 15-year multiple myeloma survivor, a 12-year survivor and an 11-year survivor, all living full lives. “It was a good day,” Lonial says.

Nooka and Lonial both credit Winship’s leaders with investing in an ecosystem that supports clinical trials. They’re grateful for partnerships with basic scientists across Emory who analyze tissue samples and help determine which drugs will best support remission. But it’s the relationships with patients, they say, that have the most enduring impact.

“It’s a multi-pronged partnership,” Lonial says. “We’re working with a very strong internal team, but we’re also partnering with other myeloma programs, with industry and—importantly—with patients and patient advocacy groups.”

Spann agrees. In her spare time, she travels to multiple myeloma conferences to share her story. She tells others with the disease to stay focused on what’s important, to have a long-term goal and strive for it.

“I’m here because of my faith and because of Dr. Nooka,” she says. “And I’m an advocate for Emory. I would not give these doctors up for anything.”

Story by Stacia Pelletier, novelist and freelance writer, is a former senior director of development for the Woodruff Health Sciences Center.

Designed by Linda Dobson

Illustration by Paul Tong

Photography by Jenni Girtman

As for Spann, she’s on another combination regimen these days, and it’s working. When she had her bloodwork done this past summer, she was declared to have a “confirmed complete response”—no myeloma cells detected in her urine, bone marrow or blood. She still comes in once a month for treatment, but she has also started volunteering at the clinic, talking with patients newly diagnosed with myeloma and offering encouragement. “I’m not the first person, nor will I be the last, to have a multiple myeloma diagnosis,” she says. “I want to let others know they’re not alone, and there’s hope.”

Winship now has close to 5,000 patients in the myeloma clinic—and counting. The increased numbers are because those diagnosed are living so much longer. That expanding timeframe fosters strong bonds between a patient and their care team. “Dr. Nooka is like family

to me,” Spann says.

Lonial recently took training fellows on rounds through the clinic. In a single day, they saw a 15-year multiple myeloma survivor, a 12-year survivor and an 11-year survivor, all living full lives. “It was a good day,” Lonial says.

Nooka and Lonial both credit Winship’s leaders with investing in an ecosystem that supports clinical trials. They’re grateful for partnerships with basic scientists across Emory who analyze tissue samples and help determine which drugs will best support remission. But it’s the relationships with patients, they say, that have the most enduring impact.

“It’s a multi-pronged partnership,” Lonial says. “We’re working with a very strong internal team, but we’re also partnering with other myeloma programs, with industry and—importantly—with patients and patient advocacy groups.”

Spann agrees. In her spare time, she travels to multiple myeloma conferences to share her story. She tells others with the disease to stay focused on what’s important, to have a long-term goal and strive for it.

“I’m here because of my faith and because of Dr. Nooka,” she says. “And I’m an advocate for Emory. I would not give these doctors up for anything.”

Story by Stacia Pelletier, novelist and freelance writer, is a former senior director of development for the Woodruff Health Sciences Center.

Designed by Linda Dobson

Illustration by Paul Tong

Photography by Jenni Girtman

Clinical trials helped Cindy thrive with incurable cancer

When Cindy was diagnosed with multiple myeloma in 2008, she was worried she wouldn’t live to raise her two children and see them grow up. After participating in several groundbreaking clinical trials at Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University, Cindy is not only still here 17 years later, but she is thriving and celebrating family milestones. Watch her powerful story of resilience, hope and the transformative impact of clinical trials on multiple myeloma.

Care tailored to your needs

Care for patients with cancer at Winship includes leading cancer specialists collaborating across disciplines to tailor treatment plans to each patient’s needs; innovative therapies and clinical trials; comprehensive patient and family support services; and a care experience aimed at easing the burden of cancer.

More from Winship Cancer Institute