Mentors Pass Along Knowledge, Skills and Wisdom

Photo: Jenni Girtman

Jasmine Miller-Kleinhenz has worked with several mentors in her 12 years at Emory, beginning as one of the university's first cohort of cancer biology students. She then participated in the R25-supported program at Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University called Citizen Science: Health and Diversity, aimed at engaging citizens and middle school-aged students in science in a meaningful way so they could imagine themselves becoming scientists. Most recently, she became a postdoctoral fellow with a five-year K99/R00 grant.

Jasmine Miller-Kleinhenz, PhD

“I’ve been really lucky to have people help guide me in how I select my mentors,” says Miller-Kleinhenz, PhD, NIH/NCI K99 Postdoctoral Fellow at Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University, “which is part of it, making sure you have someone who is going to not just align with your aspirations, but align with your central framework of who you are. I’ve been lucky to find mentors who value what I value and are also really good scientists.”

The word “mentor” comes up frequently in conversations with the leaders of Winship’s various education and training programs aimed at building the knowledge and skills of new cancer researchers, physicians, nurses, and other health care professionals, college students and even middle school and high school students. Mentoring relationships are as central to the field of medicine as are apprenticeships to other crafts requiring highly refined skills and cultivated expertise.

Reaching more than 600 learners every year, Winship’s education and training opportunities are facilitated through the Cancer Research Training and Education Coordination Core (CRTEC). Winship CRTEC activities include graduate programs, K-12 programs, educational seminars, fellowship and mentorship programs. CRTEC promotes Winship’s goal to transform cancer research, prevention, care and education through the development of a training pipeline that provides a spectrum of learners with opportunities to participate in cancer research.

U.S. News & World Report ranks Emory University among the Top 30 Best Global Universities for Oncology. “These are the world’s top universities for oncology, based on their research performance in the field,” says the magazine.

Mentorship is built in at every level of Winship’s education and training, says CRTEC’s Director Lawrence Boise, PhD, who is also Winship’s associate director for education and training and holds the R. Randall Rollins Chair in Oncology in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine. “There’s really no way to directly pay back the person who mentored you, so it’s very much a pay-it-forward environment,” says Boise.

Paying it forward means contributing toward the continuation of the high-caliber research, treatment and education that comprise Winship’s tripartite mission. “Education really represents the intersection of everything that we do here,” says Adam Marcus, PhD, Winship’s deputy director and Winship 5K Research Professor in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine. He explains that the CRTEC’s role is “to create a leadership pipeline that ensures mentorship and knowledge transfer.”

Marcus points out that Winship’s education and training efforts aren’t focused only on in-house education. “There’s also education to our middle schools,” he says, “with the idea of building a next generation of scientists and heath care providers. We’re always thinking about this pipeline to the future.”

Training new physician-scientists

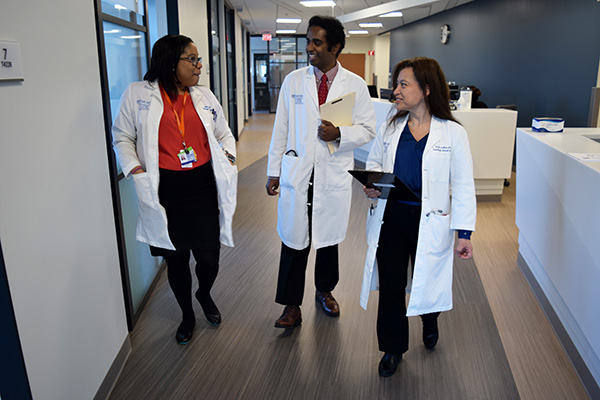

Emory Hematology and Medical Oncology Fellowship Program director Martha Arellano, MD, with former fellows Ashley Woods, MD and Deepak Ravindranathan, MD, MS.

Photo: Javier De Jesus

Winship hematologist Martha Arellano, MD, professor in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine, has been the fellowship program’s director since 2015. She notes that first-year fellows are paired with a “faculty buddy” who is a sort of “life mentor.” Next, as fellows move into their research-focused second year, they are paired with a research mentor. “The success of all of us really depends on the mentorship that is provided,” Arellano says.

Caring for a diverse population of patients is central to training the program’s now-17 fellows. Arellano, who was a fellow at Emory herself, says that something distinctive about Winship’s fellowship program is the opportunity it provides fellows to be trained in serving a very diverse population in Atlanta, where half the population are from racial minority groups. “At the end of the day,” she says, “what we’re doing is training those fellows to be excellent at taking care of all patients, no matter what walk of life they come from.” This is part of what Arellano calls the “art” of medicine, tailoring the approach to each patient as an individual.

Arellano says the fellowship program allows fellows to tailor their own education to their respective interests and professional goals. If they want to during their fellowship, fellows can pursue a master’s of science in clinical research or a certificate in translational research. “In general,” Arellano says, “one-third of the fellows pursue careers in community oncology or private practice careers. About two-thirds pursue academic careers in NCIdesignated Cancer Centers as clinical investigators or translational scientists.”

Preparing the providers

Pretesh R. Patel, MD, former director of the Radiation Oncology Medical Residency Program, meets with radiation oncology residents.

Photo: Jenni Girtman

The department’s residency program for physicians—its 16 residents make it the fifth-largest radiation oncology residency program in the United States—follows completion of a one-year internship in internal medicine. The program prepares residents for radiation oncology-certifying examinations given by the American Board of Radiology. Residents master treatment procedures taught by faculty members at the Emory Proton Therapy Center. Residents also train at two affiliated locations, Grady Memorial Hospital and Atlanta VA Medical Center.

“One of the key strengths of the program is that our trainees have access to a very wide breadth and depth of training experience with the varied Winship cancer treatment facilities,” says Pretesh R. Patel, MD, who was program director until his recent appointment as the department’s vice chair for clinical operations. “The breadth and depth of the training is really unparalleled,” he says. “It sets our residents up very well to be successful for passing their board exams.

”The Department of Radiation Oncology also offers a three-year training program accredited by the Commission on Accreditation of Medical Physics Educational Programs (CAMPEP). Twenty-nine experienced board-certified radiation oncology physicists supervise the program at Emory University School of Medicine. It aims to provide comprehensive, structured education and training in a clinical environment that will prepare residents for certification by the American Board of Radiology in Therapeutic Radiological Physics, and for a professional career in radiation oncology physics.

Anees Dhabaan, PhD, professor in the Department of Radiation Oncology, is the founder and director of the Medical Physics Residency Program. He explains that the three-year program includes a first year dedicated to research and two years spent in clinical training in medical physics—basically, he says, arranging “a complex geometry of treatments.”

Medical physics includes three branches: nuclear medicine, diagnostic imaging and radiation therapy. There are nine residents in the program—three in the first research year and six in clinic at any given time. Each resident will go through eight three-month rotations before they graduate, each one at a different location and focused on different disease sites and using different treatment modalities.

Medical physicists plan and simulate radiation-related treatment, and provide quality assurance and patient safety for the doctors. For example, Dhabaan explains, treatment with proton therapy using the linear accelerator—a massive machine that accelerates electrons that are then concentrated into a pencil-size laser beam—requires first collecting data, including the characteristics of the beam’s penetration, how far and wide it will be, how much it’s going to be in the patient and when it’s going to exit their body. All the information is fed into a computer to generate a simulation showing the expected outcomes if something is done a particular way. “We train our residents to be as precise as possible,” Dhabaan says. “When they go in the field, I sleep very well because I know their patients are safe with them.”

“Mentorship is the cornerstone of surgical training.”

“Mentorship is the cornerstone of surgical training,” says the fellowship’s director Cletus A. Arciero, MD, MS, FSSO, FACS, professor of surgery and chief of breast surgical oncology. He notes that what distinguishes the fellowship is its multidisciplinary approach to care. Arciero says, “This multidisciplinary approach pulls together all of the oncologic specialties, along with pathology and radiology, and then applies the overlay of clinical trials research and application, which is a crucial aspect of our weekly breast tumor boards.”

When it welcomes its first two residents in August, the two-year Complex Surgical Oncology Fellowship will emphasize excellence in surgical training, intellectual curiosity in research, teamwork with oncologic care providers and appreciation for the art and science of compassionate care of patients with cancer.

The fellowship’s director, Maria C. Russell, MD, Winship’s chief quality officer and professor in the Division of Surgical Oncology, says the fellowship will be distinctive in its emphasis on personalized medicine. “Cancer care must be individualized,” she says, “not only to the patient’s tumor type, stage and molecular makeup, but also must consider personal factors unique to that patient’s social situation, performance status and personal beliefs so that every patient’s care plan is specifically tailored to them.” Russell also stresses the vital role of mentorship. She explains, “A combination of assigned advisors and organic mentorship from our dedicated faculty will set our fellows up for success from a clinical, research and administrative perspective as they move into their attending career.”

A new nurse residency program for oncology

Winship oncology nurses during a team huddle.

Photo: Stephen Nowland

One way Winship is seeking to meet its nurses’ education and training needs is through a new nurse residency program for oncology. “We’ve never had this,” says Landon. “It’s enterprise- wide, so it will be for any new graduate coming in. Any inpatient unit or Winship ambulatory department nurses will come to this residency program, as well as experienced nurses who are new to oncology.”

Landon says the residency is a hybrid, using evidence-based, constantly updated training modules from the Oncology Nursing Society. Over the course of the residency year, one eight-hour class and six four-hour classes will be combined with in-person patient care. There is a class at the six-month mark to debrief because, Landon says, that’s “when people think their leaders have more confidence in them—and they have less confidence in themselves because they realize what they don’t know.” Another class at 12 months will focus on professional development. “Yes, you have your RN license, and thank goodness school is done. But we want to bring you to the next level and get you oncology nursing certified.” Passing an exam at the two-year mark will do just that.

Educating the community about cancer

Too often when someone thinks of community outreach and engagement (COE)—an activity required of all NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers—they think of health fairs or other awareness-raising activities such as screening or smoking cessation programs. Those are important, but they alone aren’t enough.

“There needs to be follow-up,” explains Theresa Wicklin Gillespie, PhD, MA, BSN, FAAN, Winship’s associate director for community outreach and engagement and professor in the Department of Surgery at Emory University School of Medicine. “Because if all we needed to do was stand in front of the grocery store and say, ‘Hey, you need to get screened for breast cancer,’ or ‘Hey, you with the cigarette in your mouth, you need to stop smoking,’ we would all be 120 pounds and eating great, no one would be smoking and we’d all be riding bicycles to work.” She adds, “It just doesn’t work that way. It’s a stepwise process, and education and awareness can be a first step.”

The next step is gathering information, such as how many people actually got a cancer screening, enrolled in a smoking cessation program or showed up to get the HPV vaccine. Gillespie says Winship’s COE has been partnering with people across the state and funds “embedded staff,” who run the programs, navigate people to their screening appointments and make sure they get into the smoking cessation program. Winship also has developed an online database, Your Connection to Early Detection, of all the facilities in Georgia that offer free or low-cost cancer screenings.

Another COE initiative is the curriculum for community education that Gillespie and Adam Marcus, PhD, are developing. Funded by an NIH Science Education Partnership Award (SEPA), it uses cancer and other big data to bring cancer research to life in a practical, real-life way for middle school girls in under-resourced schools who are interested in STEM careers.

Using real data from their own communities, the students have to go beyond merely analyzing the problem to make feasible action plans for addressing it. The final step is to share their proposed solution with people in their communities, who might say something like, “That seems like a clever solution, but here’s why it won’t work.” Gillespie says this feedback is helpful for the students. She says it also shows that cancer is “not an academic problem, but a real problem in their own backyard.”

Introducing high school students to the clinic and lab

For the first time this year a stipend was offered that expanded the number and variety of students who were able to participate in the Summer Scholars program.

Photo: Jenni Girtman

This year for the first time the program is offering a stipend to participating students, thanks to Lou Glenn, a Winship donor. “The stipend,” says Giver, “opens up the program to students who, before, may have wanted to do something like this but couldn’t because they needed to earn money over the summer.” Giver says the stipend also is helping to make the program more diverse as students from under-resourced schools are more actively applying to the program.

While Giver, who is an associate professor in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine, oversees the research lab aspect of the program, co-director Nisha Joseph, MD, oversees its clinical side. Joseph, a Winship hematologist and researcher and an assistant professor in the same department, says the Summer Scholars Research Program helps students figure out whether they are interested in becoming a physician or a scientist. “Sometimes just seeing something is so clarifying,” she says. “It seems abstract to be ‘a doctor’ or be a ‘cancer researcher.’ I feel like spending six weeks to get a little flavor really focuses them as to whether that’s what they want to do or not.”

Modeling “The Winship Way”

Carlos S. Moreno, PhD, Winship’s assistant director for education and training, helps teach the compassionate patient-centered care model we call “The Winship Way.”

Photo: Jenni Girtman

Moreno says that teaching people to provide the kind of compassionate patient-centered care we call “The Winship Way” is part of the culture at Winship. “I think all of the caregivers and the researchers, almost everyone, has been personally touched by cancer,” says Moreno, “and they understand what it’s like for the patients.”

Moreno says that transmitting the values underlying The Winship Way is “something that really is done both formally and informally. There is orientation that happens, and in our conversations those concepts come up again and again.” He adds, “I think people really take it to heart because they really do care about the patients and their care and want to put that first.”

Miller-Kleinhenz sees compassionate, patient-centered care modeled even in how Winship researchers and providers talk about their work amongst themselves. “Even when I’m in my research talking about the work,” she says, “how do I talk about a group of people? What is it that I say about them? Are they humanized or are they just data points? And if they’re data points, there’s a problem. So I think it’s really about how we treat people, but also how we talk about them and how we model that—not just in front of the patients, but throughout our spaces.”

Now that Miller-Kleinhenz finds herself in the role of mentor for others coming up in their own education and career, she has found an effective way to be helpful for her protégé. “I do a lot of formal and informal mentoring,” she says. “I work with students who are in our research group and try to figure out what it is that they need from me that will help them to thrive.” She adds, “I’ve been lucky to have good mentors, and I enjoy mentoring. No one’s an island, no one can thrive on their own. We all need people in front of us and behind us.”