Repurposing Old Drugs for New Uses in Innovative Cancer Care

Treating a disease with a drug already FDA-approved to treat something else, known as drug repurposing, can offer new treatment options for patients with unmet medical needs. It can provide advantages over new drug development in that the existing drugs’ safety and pharmacokinetic properties (how drugs move throughout and interact with the body) are already known. Repurposing drug studies also tends to have a shorter clinical development timeline than new drugs.

Vikas P. Sukhatme, MD, ScD

Best of all, repurposed drugs also may represent a more effective and affordable way to treat cancer, according to Vikas P. Sukhatme, MD, ScD, Woodruff Professor and founding director of Emory University School of Medicine’s Morningside Center for Innovative and Affordable Medicine. Sukhatme also is the cofounder of GlobalCures, a nonprofit conducting clinical trials on promising cancer therapies that are not being pursued because they aren’t considered profitable. The Morningside Center is dedicated to investigating these so-called “financial orphans,” Sukhatme says. “Generic existing/approved non-cancer drugs form the largest class of financial orphans, as do some supplements and lifestyle changes.”

How a drug becomes repurposed

Once a potential new use is identified for a drug, it then undergoes preclinical and clinical testing to evaluate its efficacy and safety for the potential new indication. If the drug is found to be effective and safe, regulatory agencies can consider approving it for the new indication—offering patients a new treatment option.

“We need to subject the many ideas we have [for repurposing various drugs] to proper clinical studies to validate or invalidate them,” says Sukhatme. “Academic health centers that house major cancer centers, such as Winship, can play a key part, especially assessing safety and feasibility and for developing biomarkers to stratify those most likely to respond.”

Sukhatme also points out the importance of engaging the community. “Our aspirational goal,” he says, “is to create a national network of caregivers in the community to do this.” Such a network would allow the researchers to collect real-world off-label treatment data with outcomes that can be extracted into a registry to complement clinical trials (registry-based studies).

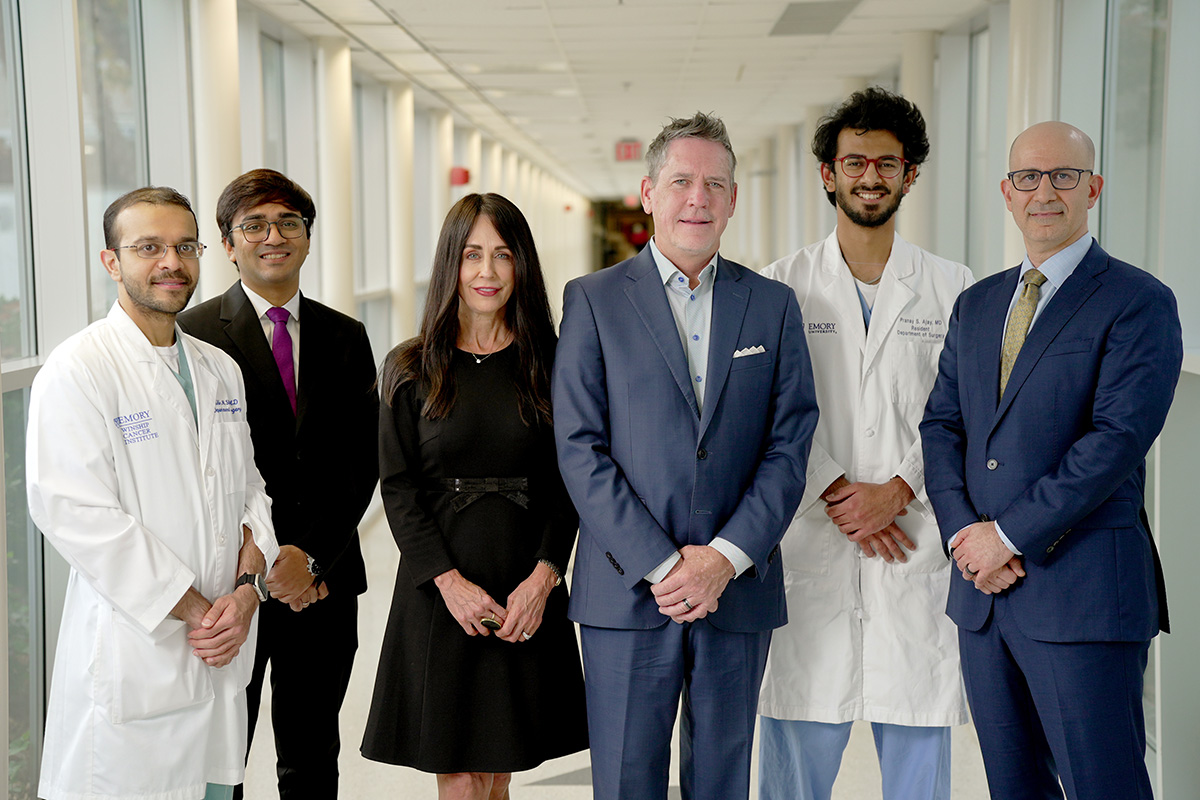

Winship leads the way

Physicians and researchers at Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University are continually studying and developing new ways to treat various cancers with repurposed drugs. Here are a few examples.

Enhancing responses to immunotherapy

The idea of treating cancer by unleashing the immune system dates back to the late 1800s and early 1900s, when William Coley injected bacteria into patients with cancer to instigate an immune response. “He had some success in multiple tumor types, but the work was largely ignored, hard to reproduce, quite toxic and not competitive with the advent of chemotherapy,” says Sukhatme. Some success was achieved years later in renal cancer and melanoma with high doses of certain immune modulators, but again it didn’t work with other tumors.

The era of immunotherapy began about a decade ago when certain solid tumor types responded to checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. This innovative treatment uses a class of drugs known as immune checkpoint inhibitors. Much like other immunotherapies, the goal of checkpoint blockade immunotherapy is to strengthen the body’s immune system and enhance its ability to fight off harmful invaders.

“The major challenge now,” says Sukhatme, “is to improve the response rate and durability of response by discovering combinations of drugs.” In fact, he says there are data for several cancer types that respond even more effectively to immunotherapy with checkpoint blockade when it’s used with certain non-cancer drugs or supplements—including histamine 1 blockers, beta blockers, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, fenofibrates, vitamin B5, magnesium and some probiotics.

Statins for head and neck cancers

Nicole Schmitt, MD, FACS

“Statin drugs appear to enhance the survival of patients with head and neck cancer, for reasons that we do not fully understand,” says Nicole Schmitt, MD, FACS, co-director for translational research in Winship’s Head and Neck Program and associate professor in the Department of Otolaryngology at Emory University School of Medicine. Data from laboratory and animal studies suggest that statin drugs can “directly kill” cancer cells—potentially by ‘starving’ them of the cholesterol-related byproducts they need—and enhance immune cells’ ability to fight the cancer as well.

Statin drugs offer significant benefits for treating head and neck cancers. Large clinical studies show they improve survival. Animal studies, though not yet confirmed in human studies, suggest they improve responses to immune therapy. Human studies show they reduce severity and incidence of hearing loss in patients treated with chemoradiation. A phase 2 human study in Europe also has confirmed they reduced the severity of radiation fibrosis, a skin condition affecting people treated with radiation. “Statins may improve not only quantity but quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer,” Schmitt says.

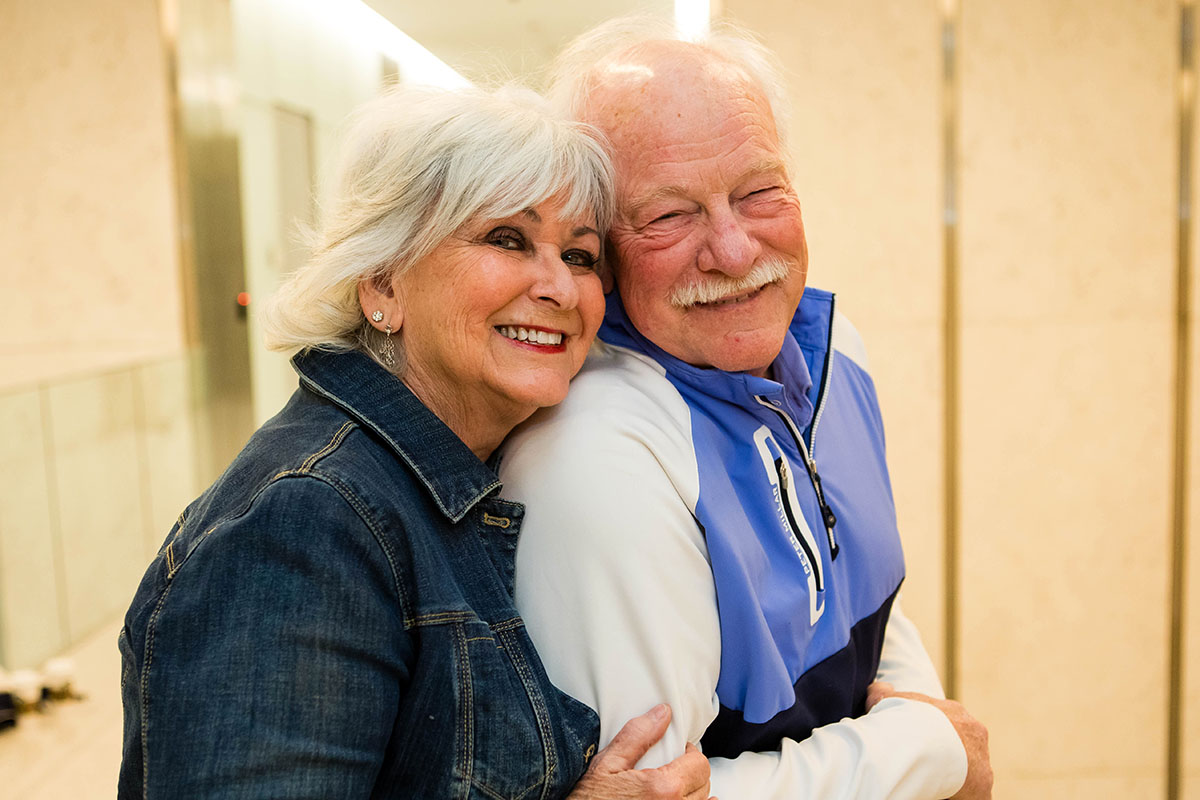

Beta blockers for multiple myeloma

Beta blockers are typically prescribed to treat high blood pressure or other cardiovascular-related issues such as angina or arrhythmia. Winship researchers have studied another potential use for propranolol—a beta blocker often prescribed for heart problems, anxiety or migraines: as a treatment for multiple myeloma, a cancer of the blood’s plasma cells. Studies show beta blockers like propranolol may increase multiple myeloma cells’ sensitivity to specific therapeutics.

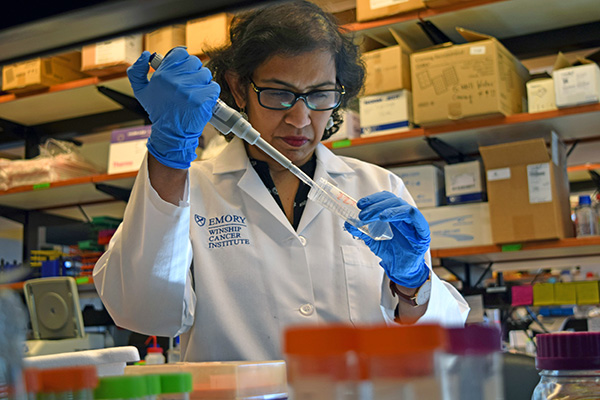

Malathy Shanmugam, PhD, MS

“Beta blocker effects on cancer are likely complex, targeting the cancer directly and indirectly,” says Malathy Shanmugam, PhD, MS, a member of Winship’s Cell and Molecular Biology Research Program and associate professor in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine. Her team investigates based upon the premise that cancer causes stress, which leads to inflammation within the bone marrow—where multiple myeloma cells reside—making the bone marrow microenvironment even more susceptible to cancer.

Specific beta blockers can shut down the signals that promote the inflammation and related tumor growth. Although studies led by Shanmugam in this area are promising, more research is needed to determine the significance of the findings, and the ideal uses for the best outcomes. Shanmugam notes that one published study shows that the beta blocker propranolol—typically used to treat high blood pressure—improves the progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival of patients with multiple myeloma.

The question now is which patients benefit the most from beta blockers and which beta blocker is most effective. Although several clinical trials are under way in different disease contexts, the use of beta blockers in myeloma has not been extensively tested. “Future studies can allow for selective beta blockers to be repurposed for multiple myeloma therapy in specific contexts,” Shanmugam says, including an LLS grant-supported study she is leading through 2025, “Investigating anti-neoplastic effects of beta blockers in multiple myeloma.” She adds, “Any knowledge we gain about how beta blockers can prevent development and progression or improve sensitivity to existing therapy can help in repurposing these drugs for multiple myeloma therapy.”

Psychotropics for acute myeloid leukemia

Kevin Bunting, PhD

Another potential breakthrough in repurposing drugs for cancer care involves the possible application of a drug used to prevent tics in patients with Tourette’s Syndrome. It may potentially provide some benefits to patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a cancer of the bone marrow that interferes with the normal production of red and white blood cells and platelets. The research on potentially repurposing these psychotropic drugs is in its early stages, according to Kevin Bunting, PhD, member of Winship’s Cell and Molecular Biology Research Program, Aflac Field Force Cancer Innovative Therapy Chair in the Aflac Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, and a professor in the Department of Pediatrics, Division of Hematology and Oncology, at Emory University School of Medicine.

Bunting says the work is limited to cell lines in the lab. Although it shows “proof of concept,” he says they need to optimize drug delivery to avoid side effects from the combination therapy. It will be necessary to formulate the drug in a particular way, or use nanoparticles, to deliver it to humans at a therapeutic dosage. But human patientlevel data are not yet available. “It’s early translational research,” Bunting says, “which is inherently hard to predict going forward.” He adds that he would like to return to this therapeutic work in the future.

Looking ahead to future repurposed drugs for cancer

Sukhatme says Winship is running half a dozen repurposed drug trials, and the number is expected to double this year. Research continues to provide answers as to the best uses for repurposed drugs, even the best time of day to take them.

Sukhatme is optimistic about the future of repurposed drugs to prevent many types of cancers from recurring. “We expect all types of cancer to benefit [from repurposed drugs],” he says. “We have ideas for drugs to be given at the time of surgery for cancers that have not metastasized macroscopically, that could prevent or delay cancer recurrence. We have ideas for interventions that will make checkpoint blockade [immunotherapy] more efficacious. And we have ideas for treating metastatic disease with drugs that prevent a cancer cell from adapting to the harsh environment where it exists when it forms a tumor mass.”

For now and into the future, Sukhatme adds, “Randomized studies are sorely needed. The gold standard of scientific research, such studies are the only way we can find out if a drug is effective, more effective than existing drugs or can be repurposed for other uses.”