The Magic of Nature’s Pharmacy: Lessons from the Yew Tree

In a small churchyard in the countryside village of Fortingall, Scotland, there stands an ancient tree—perhaps the oldest in Europe—protected by a stone wall.

Numerous “magical” plants from folklore remain to be studied. The key is in our willingness to look.

To reach it, you must first walk through a small cemetery, its grounds covered in lush green grass, and moss filling the spaces between headstones carved with names and symbols from a time long past. Known as the Fortingall Yew, this particular tree is estimated to be thousands of years old. In Celtic lore, the yew tree symbolizes death and resurrection and is used in rituals linked to magic, fertility and power.

As a medical ethnobotanist, I have visited this tree and many other “magical” plants across the globe in my search for knowledge about the treasures the plant kingdom has to offer for the future of our medicines.

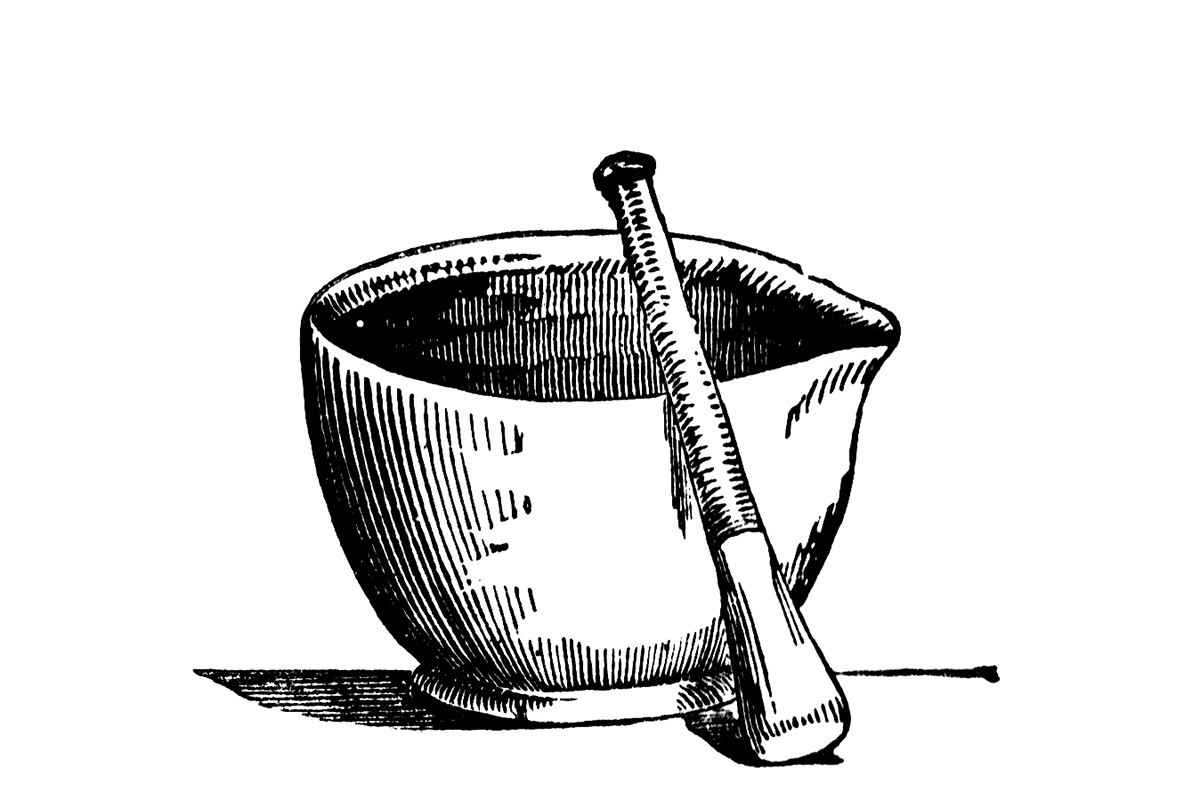

The English yew tree (scientific name: Taxus baccata) is special not only because of its long lifespan and ties to magic, but also for its toxic properties. Its evergreen needles, bark and seed cones are full of poisons. The only part of the yew that is not poisonous is its fleshy red aril, which surrounds the single seed of each cone. This part is edible if you spit out the seed. The wood of the English yew is easy to carve and was the preferred material for crafting early musical instruments such as the lute and the infamous medieval English longbow.

In the 1950s, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) established the Cancer Chemotherapy National Service Center to develop new cancer therapies. Initially focused on testing known and synthetic compounds, the program expanded in the 1960s through a partnership with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), exploring natural sources for cancer cures. Between 1960 and 1981, over 30,000 samples were collected for cancer testing.

One notable sample was from the Pacific yew (Taxus brevifolia), a relative of the English yew, collected in Washington State in 1962 by USDA botanist Arthur Barclay. In 1964, chemists Monroe Wall and Mansukh Wani, supported by an NCI contract, discovered that the yew tree extract was toxic to living cells, isolating the most potent compound, paclitaxel.

Paclitaxel’s 30-year journey from discovery to FDA approval faced numerous challenges. Selected for clinical development in 1977, it was approved for treatment of ovarian cancer in 1991 and for breast cancer in 1994. Biochemist Susan Horwitz, in 1977, elucidated how paclitaxel impedes cancer growth by arresting cell division and inducing cancer cell death while stabilizing the microtubules, a mechanism distinct from other drugs.

Another major hurdle was production scalability, as the slow-growing yew tree couldn’t supply sufficient bark. The first breakthrough came from the toxic needles of the English yew, commonly used in landscaping. Chemists could convert a similar compound from garden clippings into the drug. Today, paclitaxel (also known as Taxol®) is mass-produced in fermentation tanks with plant cells serving as mini drug factories. It has been used to treat more than 1 million patients, making it one of the most widely used antitumor drugs.

Like the yew tree’s story, other vital cancer medications were discovered by examining medicinal plants and optimizing their active chemical structures as drugs. Consider etoposide, derived from the mayapple plant, used to treat cancers like testicular, prostate, bladder, stomach and lung cancer. Another example is the vinca drugs from the Madagascar periwinkle: vincristine, effective against leukemia, lymphoma, neuroblastoma and Wilms tumor; and vinblastine, used for Hodgkin’s lymphoma, non-small cell lung cancer, bladder cancer, brain cancer, melanoma and testicular cancer.

There are an estimated 374,000 plant species on Earth, with about 9% (over 34,000) documented for use in various traditional medicines. However, a vast majority of these medicinal species (98%) have not yet undergone rigorous scientific study to identify their active molecules or to evaluate their safety and effectiveness in treating human diseases.

This scenario presents a vast, untapped reservoir of potent chemistry in nature, waiting to be explored. Numerous “magical” plants from folklore remain to be studied. The key is in our willingness to look.

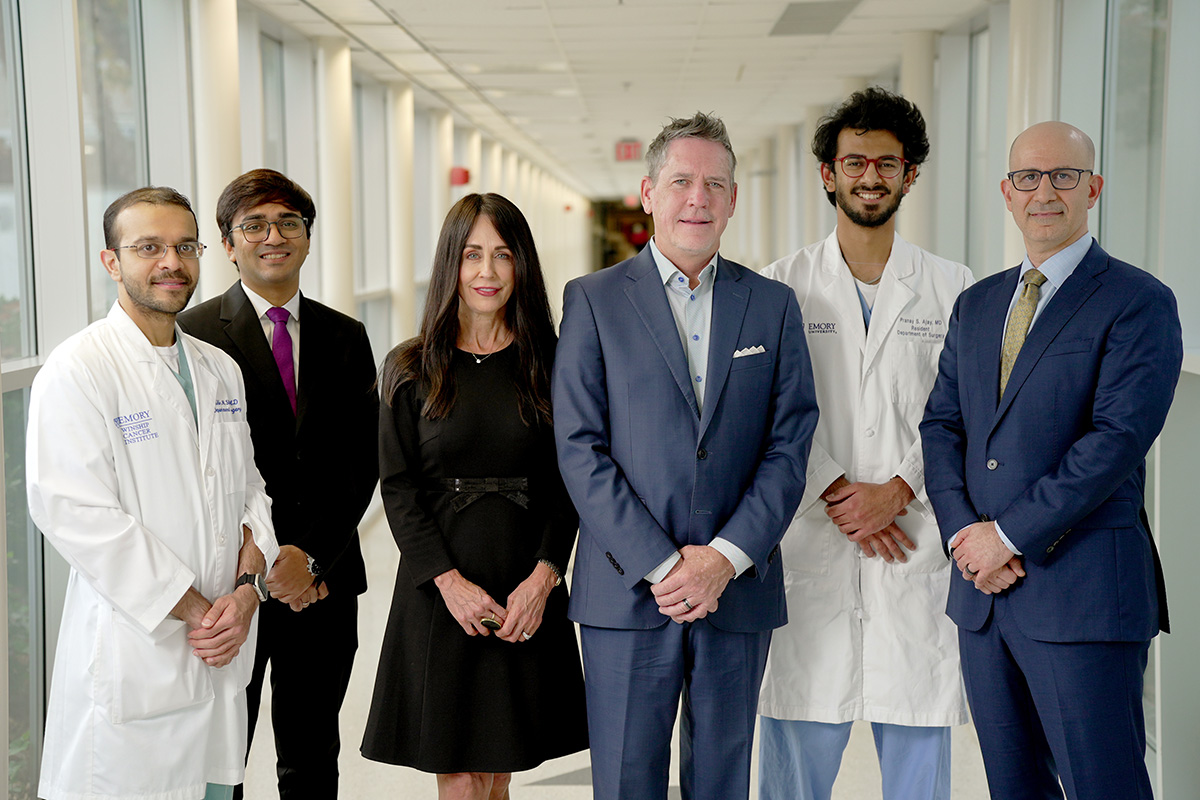

Cassandra Quave, PhD, is a medical ethnobotanist focused on documenting and pharmacologically evaluating plants used in traditional medicine. A member of the Discovery and Developmental Therapeutics Research Program at Winship Cancer Institute, she serves as the curator of the Herbarium, the Thomas J. Lawley, MD, Professor of Dermatology and associate professor of dermatology and human health at Emory University School of Medicine, where she is also the assistant dean of research cores.