Winship Navigates Industry Drug Shortage

When tornado damage in the summer of 2023 shut down a pharmaceutical plant in North Carolina, the pharmacy staff at Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University quickly took notice. Like meteorologists tracking a storm, they began to calculate how the plant closure might affect the supply of drugs for Winship patients.

Fortunately, the plant closure was short lived. In late September, the facility reopened and resumed production of medications to meet patient needs and replenish hospital system inventories on a priority basis.

Ryan Haumschild, PharmD

Unfortunately, though, drug shortages are commonplace in the United States today. At the end of June 2023, more than 300 drugs were in short supply, based on quarterly data from the University of Utah Drug Information Service.

“Drug shortages are something we’ve always had to deal with,” says Ryan Haumschild, PharmD, director of pharmacy for Winship Cancer Institute and Emory Healthcare. “It’s become more of an issue in the past 10 years.”

Why is there a shortage?

The factors driving these shortages are varied: manufacturing issues, production delays, regulations that slow the expansion of production facilities overseas, increases in drug demand, discontinuation of a particular drug and the occasional natural disaster, like the tornado in North Carolina.

Most experts point to the generic drug market as the primary cause. Because these low-cost drugs yield low profit margins, only a few companies make them. “If one of those companies closes because of manufacturing problems, it impacts the sustainable supply chain for that medication,” Haumschild explains.

In recent months, the United States has experienced a shortage of 15 cancer drugs caused by manufacturing and supply chain issues. Three of these drugs—cisplatin, carboplatin and methotrexate—are generic chemotherapy drugs used safely for decades to treat patients with cancer.

Late last year, the manufacturing plant in India that makes cisplatin and methotrexate ceased production after failing to meet U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) quality control standards. Up until then, the company supplied 50% of these drugs in this country. Additionally, the cisplatin shortage led to increased demand for carboplatin as an alternative chemotherapy treatment.

The FDA—backed by President Biden’s commitment to end cancer through the Cancer Moonshot—has taken steps to help alleviate these shortages. Actions include working with cancer drug manufacturers to increase production capacity and bring companies that had stopped producing cisplatin and carboplatin back to the U.S. market. The FDA also cleared the way to import more cisplatin from overseas and worked with five manufacturers to increase methotrexate supplies.

Jonathan L. Kaufman, MD

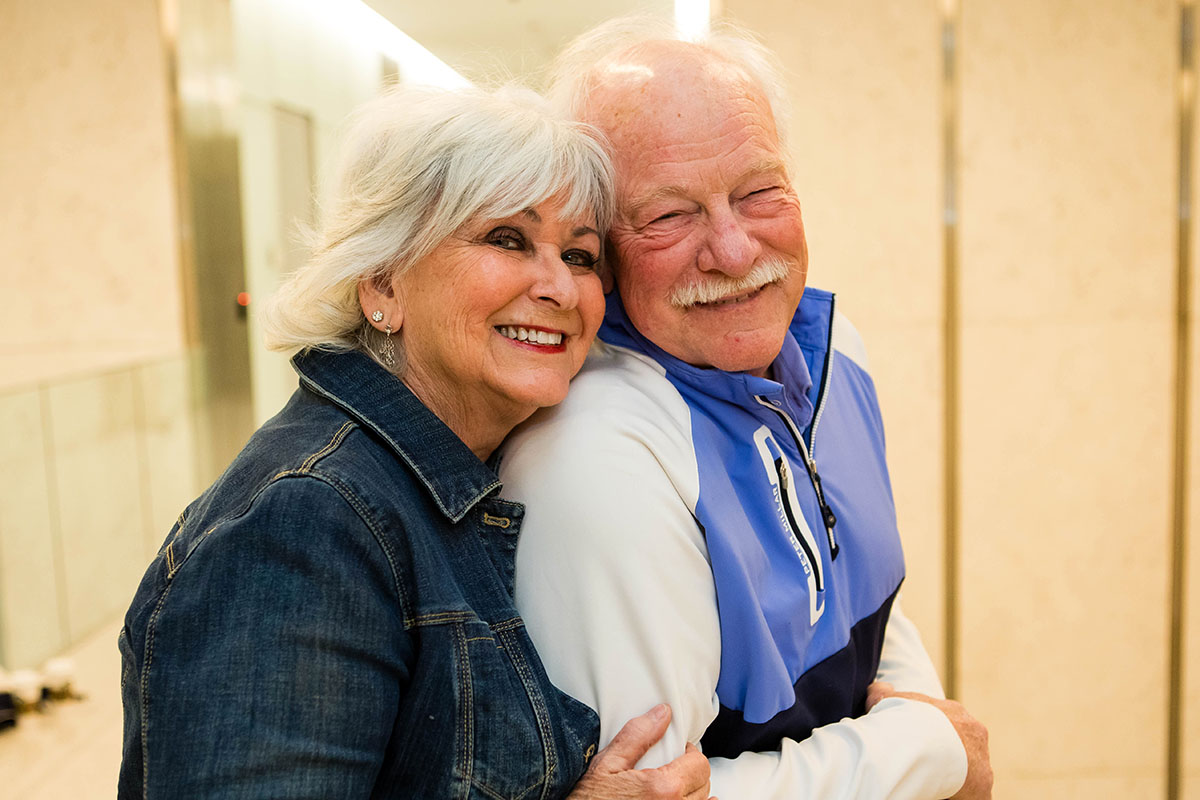

“So far, we haven’t had any issues with our supply of immunotherapy drugs,” says Jonathon Kaufman, MD, medical director and section chief of the Winship Cancer Institute Ambulatory Infusion Centers. “Carboplatin has been the most concerning, and we’ve asked our teams to use a non-carboplatin approach to treatment when they can.”

Kaufman adds that during summer 2023, there was an issue with fludarbine, a chemotherapy drug used in patients with hematologic malignancies. “Other cancer centers had experienced a shortage, which affected us very late,” Kaufman says. “We did have to initiate our shortage plan, but we’ve overcome that. We had to shift treatment using another drug for a very short time.”

By nature, the term “drug shortage” is concerning. “But ‘shortage’ doesn’t mean that a medication is unavailable,” says Kaufman. “If we did not implement changes in treatment when they are needed and no new medication was available, then it’s possible that medication would not be available in the future. Fortunately, with our dedicated approach, we have not faced this situation.”

Planning for drug shortages

Drug inventories can vary among the nation’s comprehensive cancer centers at any given time. “When we’ve had a shortage of a medication, our cancer center partners have stepped in to help when their inventories were okay,” says Kaufman. “We’ve reciprocated when they have a need.”

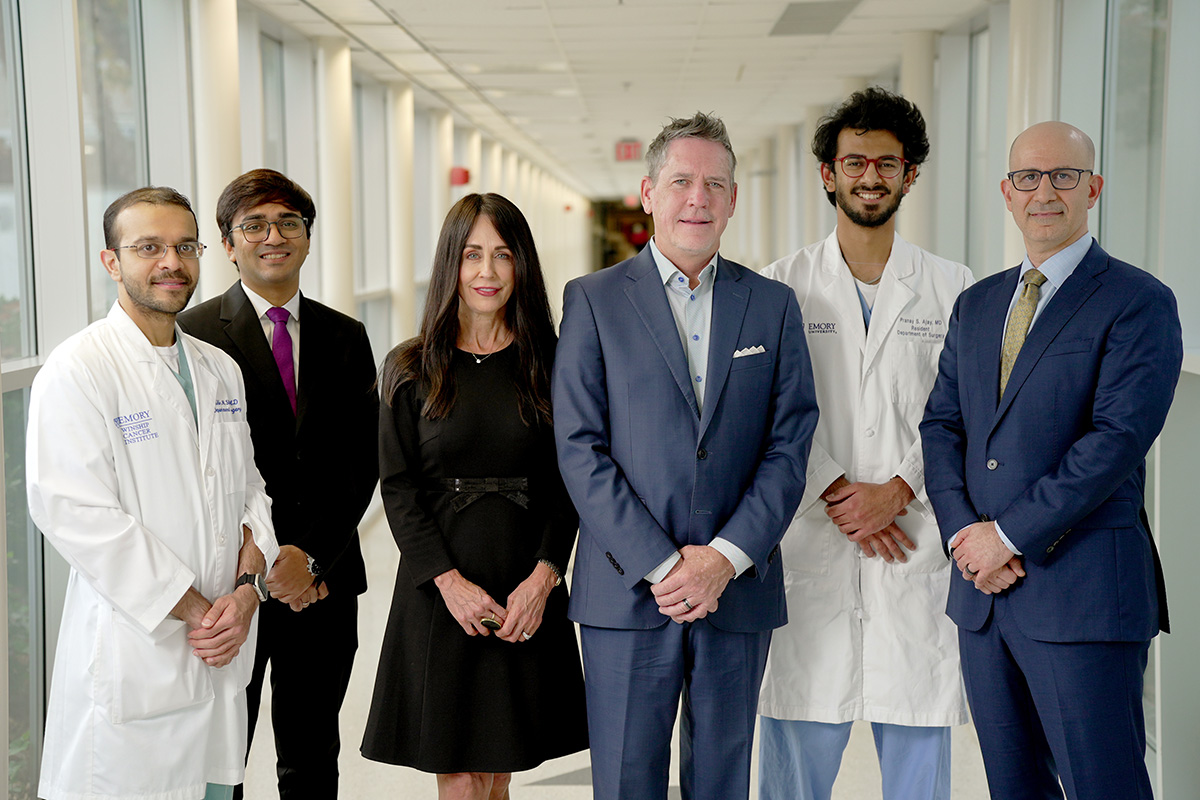

While the shortage of immunotherapy drugs has been challenging for cancer centers in general, Winship has managed any shortages through a rigorous approach based on preparation, collaboration and transparency.

“Dr. Haumschild and our clinical and operational pharmacy managers, pharmacy technicians and buyers do a great job of monitoring drug supply data and staying ahead of things by making sure we have an adequate supply of medications and that we’re prepared for shortages,” says Kaufman. “We have the ability to withstand shortages up to four months. If we reach that point, we then consider other drug treatment options so that we stay prepared.”

Haumschild and the Emory Healthcare pharmacy leadership team are constantly looking ahead—anticipating shortages, staying up to speed with manufacturers, taking the pulse on drug volumes nationally and locally and participating in the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists and other organizations. Once a week, Haumschild and Suresh S. Ramalingam, MD, Winship’s executive director, join other comprehensive cancer center leaders on a conference call with FDA leaders to discuss drug shortage issues and strategies.

“We work very hard to stay ahead of drug shortages, including the current shortage of chemotherapy drugs,” says Haumschild. “At any point in time, some supplies become more stable while others may not. We have to keep physicians and everyone else up to date.”

When a potential drug shortage arises, Haumschild, Kaufman and others work closely with Winship’s disease teams (for lung, breast, lymphoma, myeloma and other types of cancer) to determine how best to conserve current drug supply and, if needed, manage changes in treatment from a medication on shortage to one with equivalent benefits for patients.

All disease teams follow best practice guidelines for drug shortages developed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the Oncology Nursing Society. They also work closely with Winship ethicist Rebecca Pentz, PhD, to determine the best way to steward drug supply, now and in the future, to ensure ethical and equitable treatment for patients.

Open communication is key to managing any drug shortage issue. “We’re transparent with physicians and we’re transparent with patients,” says Kaufman. “We inform patients when a change in treatment is needed, and why, and assure them the change is appropriate and does not compromise their care.”

Each week, Haumschild takes part in another Emory Healthcare system pharmacy conference call to monitor the landscape of drug shortages as products on shortage change frequently due to manufacturer issues or demand.

“At Winship, we’ve really been lucky,” he says. “We have not had to withhold care from patients because of drug shortages. That’s because we’re so intentional about staying ahead of these shortages as much as possible every day.”

“I like to think we are a duck that sits gently on top of water,” says Haumschild, “but we’re pedaling like crazy underneath so our patients have a seamless experience and the best possible outcomes they can.”